John-Paul Himka

The current war being waged on Ukraine has provoked a surge of support for the people of Ukraine. To help a greater understanding of Ukraine we are hosting an online event on 21 April 8:00 PM (London time) with the Ukrainian historian John-Paul Himka: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE. In advance of the event we publish below A Brief History of Ukraine, by John-Paul Himka which can assist our movement in its understanding of the historical context of the war being waged on Ukraine. To join the event please register by following the link here: REGISTER

Preface

This was written as Russia’s aggressive war has been raging in Ukraine. I think a relatively short history of Ukraine in English, one that can be read in a couple of hours, can help people orient themselves to the issues. Every historical survey is, of course, an interpretation and a simplification. There is no way around that. I hope I have picked the most important things that need to be explained. I have included a single illustration, of the Eurasian steppe, which is in the public domain. It is easy to find historical maps on the Internet, and readers are advised to do so as required. I thank my readers Beverly Lemire, Morris Lemire, and Alan Rutkowski who have helped me prepare a more readable text. I also thank Chrystia Chomiak for formatting the text.

Edmonton, Alberta, March-April 2022.

988

Everyone knows about the Vikings who roamed the seas. They are famous both as ferocious warriors and also as explorers of the farthest reaches of the northern hemisphere. They established short-lived settlements in North America and Greenland as well as one that survives to the present – Iceland. But there were also Vikings who roamed the rivers. They set out from Scandinavia in the ninth century, exploring the waterways that coursed through the East European forests and steppe until eventually they were able to sail to the two most magnificent and richest cities of that era, Constantinople and Baghdad. They brought goods, especially furs, to trade in Baghdad and were able to acquire luxury items that came from China via the Silk Road. They traded also in Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine empire. Here, in fact, they served the Byzantine emperor as soldiers in his Varangian Guard. “Varangians” was how the Vikings who explored the East were called. Persons familiar with Canadian history will recognize that they were much like a medieval version of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The Varangians/Vikings established new settlements or took over existing settlements along the way, notably in Novgorod on the Volkhov River (today in Russia) and in Kyiv on the Dnipro River (today the capital of Ukraine). One Varangian leader by the name of Riuryk established a dynasty that ruled a vast realm known as Rus’. A derivative of the name Rus’ has given us the English word Russia, but other derivatives, such as Rusyn or Rusnak, were ethnonyms in western territories of Ukraine into the twentieth century and up to the present.

According to the Rus’ chronicle, in 988, one of Riuryk’s descendents, Volodymyr (Vladimir in Russian) accepted Christianity and baptized the Rus’ people. It is uncertain whether this really happened in that particular year and how it happened. The sources are too fragmentary for definitive answers. But subsequent developments make the meaning of 988 clear.

Rus’ adopted Christianity from the Byzantine empire. At the time it did so, there was no division in the Christian church, no schism between East and West. But in the following centuries relations between the two large branches of Christianity deteriorated: there was a formal schism in 1054, and during the crusades Western Christians attacked the Byzantines many times, creating a wide breach between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Some historians of Ukraine have reflected that Volodymyr’s was an unfortunate choice, since the West was to emerge as a global hegemon while the East was reduced to a stagnant subaltern. Perhaps.

The transition from a pagan nation into a Christian nation meant a civilizational transformation. It demanded the erection of churches. The magnificent St. Sophia Cathedral, still standing on Volodymyr Street in Kyiv, was built by Volodymyr’s son, Yaroslav, in the eleventh century. The rulers of Rus’ and its principalities built cathedrals and churches throughout the land. Each one would require architects, engineers, and painters. At first much of this expertise had to be imported from Constantinople, but the local Rus’ soon learned the requisite skills from the Byzantine masters. Things were moving fast beyond what the Viking explorers and the largely agricultural populace of Rus’ could do before Christianization. The rulers also generously founded and funded monasteries. These were beacons of enlightenment in the land. The monks penned the chronicles, copied sacred texts, investigated the heavens (both theologically and astronomically), kept libraries, and produced sacral art. At the secular courts, the first Rus’ law code appeared.

Crucial to the intellectual awakening of Rus’ and to the development of a common culture was the adoption of writing in the Slavic language. The population of Rus’ did not consist of one kind of people. There were different tribes speaking different Slavic dialects, and also peoples who spoke other tongues, including languages that were not Indo-European. In those bygone times, people did not always write in the languages they spoke. Written languages encompassed differing populations and forged commonalities. We can think of the spread of Latin across much of Europe and the spread of Arabic across the Middle East and Africa. We know that much of Rus’ already spoke Slavic dialects on the eve of Christianization, but large parts of it had to be conquered linguistically and civilizationally by written Slavic. Rus’ adopted its writing system from the Byzantines’ rivals, the Bulgarians. The Bulgarians wrote in a language now known as Old Church Slavonic. Texts that the Bulgarians translated from the Greek or wrote themselves were copied and sent to the monasteries and courts of Rus’. Very quickly the Bulgarian Slavonic began to adopt features of the local Rus’ dialects. Certain characteristics of modern Ukrainian can be traced back to some of these early texts.

All of this civilizational development was possible because of the riches Rus’ accrued as a center of trade between the Byzantines and caliphates to the south and the Baltic regions to the north. Novgorod became part of the Hanseatic League, one of medieval Europe’s richest commercial networks.

Russian and Ukrainian historians have debated whether Kyivan Rus’ was Russian or Ukrainian. Most historians today consider this to be a false choice. They feel that the major events that created differentiated Russian and Ukrainian nationalities came later, after the rise of a Muscovite state and after Ukraine was incorporated into Lithuania and Poland. Old Rus’ had certain things in common: a dynasty, a writing system, and a religion. There were also innumerable variations on a local scale. Rus’ was like the empire of Charlemagne. The Carolingian state encompassed territories that today make up France and Germany. It was an ancestor of both French and German culture. Rus’ was something akin this.

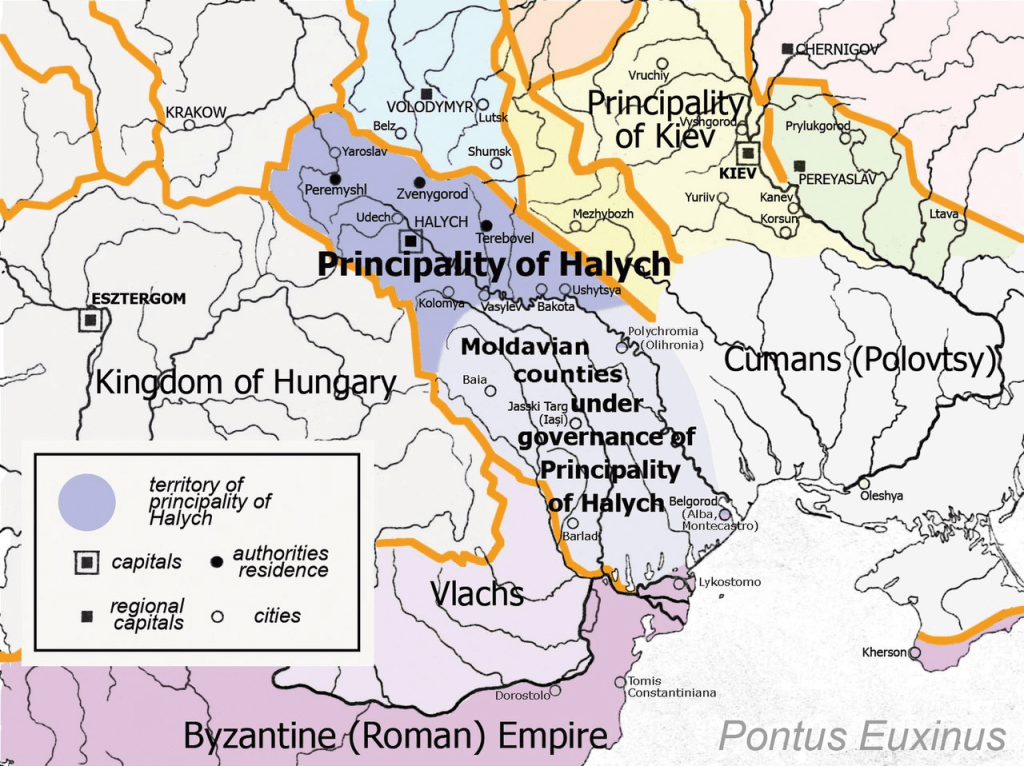

In another respect too Rus’ was similar to the Carolingian realm. Charlemagne was able to hold his large empire together as long as he lived. So was Volodymyr. But the children and grandchildren of Charlemagne divided the lands among themselves, reducing the state to small principalities, ruled by Carolingians but no longer united. Similarly in Rus’, civil war among his sons followed Volodymyr’s death. And every generation afterwards divided Rus’ into more and more principalities. Kyiv was no longer the capital of Rus’, but the capital of the Kyiv principality. As the richest and most prestigious of the principalities, it was often attacked by rival principalities. For example, both the Galician-Volhynian principality, located in what is today Western Ukraine, and the Vladimir-Suzdal principality, which eventually evolved into the Grand Duchy of Muscovy, attacked Kyiv. Attempts by the Kyivan princes to restore unity were thwarted by ambitious rivals.

1240

The internal divisions in Rus’ were dangerous. To the south of the Rus’ heartland was the Eurasian steppe, a large, grassy plain stretching from northeast China into central Hungary.

Horseback nomads had been crossing the steppe for millennia before Rus’ was even Christianized. Some of these nomads were of Iranian stock, others Turkic. Different waves of nomads appeared at different times: Scythians, Huns, Khazars, Pechenegs (or Patzinaks), and Cumans (or Polovtsi). They sometimes raided the Rus’ as they were portaging their commercial vessels along the Dnipro River. The nomads were long more of an irritant than an existential threat. In fact, during the internecine wars in Rus’, the princes sometimes made alliances with the nomads against their fellow Rus’.

Then a new type of nomad appeared. A charismatic leader in Mongolia by the name of Temujin, later known as Genghis Khan, put together a huge fighting force that undertook a systematic conquest of neighboring realms. Genghis Khan was a farsighted leader. He drafted Uighur Turks to design an alphabet and writing system for the Mongol language. He initiated written legislation. He set up an efficient postal system. Most important, he took over large parts of China in the 1220s. He recruited Chinese experts to develop his intelligence network and weaponry. The Mongols had gunpowder before any of the Europeans, including Rus’.

Several Rus’ principalities as well as some of the nomads of the Ukrainian steppe first confronted the Mongols in battle in 1223. They were roundly defeated by what was essentially a Mongol scouting party. The Mongols withdrew from Rus’, but learned enough about the realm and its riches to decide it was worthy of full-scale invasion. A massive Mongol army was gathered under the leadership of Genghis Khan’s grandson Batu Khan. It initiated its conquest of Rus’ in 1237 and reached Kyiv in 1240. The Mongols laid waste to Kyiv and its environs, reducing the Rus’ capital to something like a ghost town and depopulating much of the countryside. Surviving Rus’ principalities surrendered to Mongol suzerainty. Although the Mongols were ruthless in war, they understood the advantage of leaving most of their conquered populations alive in order to tax them.

But the same problem that had plagued Rus’ and the Carolingian empire affected the Mongol empire. It was unable to retain unity after the death of its founder, Genghis Khan. Although the great Khan had died already in 1227, the fracturing of his empire came a few decades later; civil war among his descendants broke out in 1259. The steppe north of the Black Sea as well as the peninsula of Crimea fell under the control of the Golden Horde, one of the successors to the Mongol empire. The remnants of the Mongol army were to remain in the Rus’ steppe for half a millennium. Eventually the Golden Horde became the Crimean Khanate under the suzerainty of Ottoman Turkey. Most of the “Mongols” here were actually Turkic-speakers, descendants of the Tatar tribe that Temujin had subdued even before he was proclaimed Genghis Khan. After the Ottoman Turks took Constantinople in 1453, the Tatars of the steppe engaged in regular raids of the Slavic territories in the north to capture slaves for the Ottoman markets.

After the fragmentation of the Mongols, it was possible for other regional powers to take the territories north of the steppe. Poland was able to acquire the principality of Halych, or Galicia, in the mid-fourteenth century. Around the same time, Lithuania took the nearby principality of Volhynia as well as Kyiv. The Lithuanians, whose state had not yet officially converted to Christianity, adopted the Slavonic writing system from their new subjects, the ancestors of the modern Belarusians and Ukrainians. Lithuanian princes also began to convert from their pagan cult to the Eastern Orthodox church and funded the construction of monasteries and churches.

The northeastern Rus’ principality of Vladimir-Suzdal eventually moved its center to Moscow, which became the capital of the Grand Duchy of Muscovy. Muscovy remained the longest under Mongol suzerainty, becoming fully independent only near the end of the fifteenth century. Although cultural and religious relations continued among all the Rus’, the political divisions that arose after the Mongol invasion are considered by historians to be instrumental in the formation of separate Ukrainian and Belarusian nations on the one hand and Russians on the other. Historians of the early modern era generally refer to the Rus’ in the Polish-Lithuanian political sphere as “Ruthenians.” Ruthenian scholars and churchmen moved freely between Vilnius and Kyiv, creating a closely linked religious culture. But other historical processes were at work that were rapidly differentiating the Ukrainians from their Belarusian coreligionists.

1648

In the sixteenth century Spanish conquistadors subdued the Aztec and Inca empires in what for them was the New World. They looted so much silver and gold that Europe was struck by its first major inflation. Western Europe also began to develop a new economic system – capitalism. The old feudal structure, including serfdom, was breaking down. The new money and new inventions, such as the printing press, promoted what historians have often described as the Rise of the West.

Things were rather different in the eastern part of Europe. No state undertook overseas exploration. And instead of the collapse of the feudal system, a new and much more intense form of serfdom was coming into being. Beginning roughly in 1500, noble landowners throughout Poland, which at this time included Ukrainian-inhabited Galicia, began to mark off large agricultural estates for growing grain and to force the local farming population, the peasants, to work on them. The manorial estates were generally situated near a river so that the grain could be shipped to the main artery, the Vistula River, and sent downriver to the port of Gdańsk and then on to the burgeoning markets of Western Europe. It was an excellent deal for the landowners, and some noble families became so rich that they held hundreds of such estates and maintained their own armies. But it was not such a good deal for the peasants.

The enserfed peasants were expected to feed and clothe themselves from their own minor landholdings. This self-sufficiency was the major factor that differentiated their situation from that of the new kind of slaves being imported to the Americas from Africa. The serfs were tied to the land; they had no right to leave. They were taxed by their landowners, who collected money, honey, chickens, sheep, or whatever the peasants of the region produced. Mainly, however, the landlords taxed the serfs by making them perform all the labor on the manorial estate. Serfs also had a few days to work on their own plots of land. This new serfdom became more onerous as time went on. Serfs who objected to the system were beaten and imprisoned. More serious violations resulted in their execution, since nobles wielded the jus gladii, that is, the right to condemn their subjects to death.

The only escape from this system was to migrate to dangerous areas to the east and south, to territories where the Tatars roamed. Escaped serfs, but also adventurous nobleman, moved into the steppe, the Wild Fields as they were known back then. The migrants hunted, fished, and trapped for furs. They travelled to the Black Sea coast to collect salt for sale in the market towns of Poland and Lithuania. These frontiersmen learned to fight, since they were constantly encountering Tatar bands who wanted to sell them in the lucrative Ottoman slave market. The frontiersmen banded together at fortified locations, the most famous of which was the Zaporozhian Sich near the rapids of the Dnipro River. They came to be called Cossacks (Kozaky in Ukrainian), from a Turkish word meaning adventurer or freebooter. The Cossack heritage was a factor differentiating Ukrainians from Belarusians, although both shared the same “Ruthenian” religious culture.

Poland and Lithuania had been joined in a personal union since the end of the fourteenth century, i.e., the King of Poland was also the Grand Duke of Lithuania. But when the dynasty that produced the joint ruler was about to die out, Poland and Lithuania agreed to a union that did not depend on dynastic ties. The Union of Lublin in 1569 created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, at that time the largest and most powerful state in the East of Europe. A provision of its terms that was to have major consequences for Ukraine was the removal of Ukraine from the Lithuanian Grand Duchy to the Polish Crown. One of its effects was that what is now Belarus and what is now most of Ukraine ended up in separate political jurisdictions.

A more significant consequence was that the Polish nobles began a concerted campaign to establish latifundia in the relatively unpopulated Ukrainian territories north of the steppe. They often enlisted the Cossacks to help them in the wars with Turkey and the Crimean Khanate that their eastward expansion provoked. The lords lured peasants from overpopulated Galicia and elsewhere to their new agricultural enterprises. At first the peasants were granted a period of freedom from taxation and labor duties, but after a few decades serfdom was ruthlessly imposed on the population. Again, the landlords flourished and the common people suffered. Runaway serfs joined the Cossacks, and social differences began to take on more and more of an ethnic coloring, with landlords – even if of Ruthenian origin – embracing Polish culture and Roman Catholicism while peasants and Cossacks retained the Ukrainian language, which by then was fully formed, and the Orthodox faith.

Cossack revolts and peasant revolts erupted from the end of the sixteenth century on. A major grievance of the Cossacks was the Commonwealth’s policy of registration. When war broke out with Turkey and the Crimean Khanate, which happened frequently, the Cossacks would be registered and paid wages. But after a war was over, the state would reduce the number of registered Cossacks, and landlords would attempt to enserf the unregistered.

This social and military tinderbox also had a religious aspect. When the Lithuanian grand dukes first sat on the Polish throne in the late fourteenth century, they funded various Orthodox projects. But soon they adopted Roman Catholicism, and Ruthenian Orthodoxy began to be treated as a stepchild. Orthodox states neighboring Poland-Lithuania, namely Moldavia to the south and Muscovy to the northeast, built stone monasteries and churches and funded libraries and icon painting workshops. In Moldavia, the monasteries were both centers of learning and fortifications. In Poland-Lithuania, however, the Orthodox church was poor and its clergy relatively uneducated. The Polish state appointed laymen as bishops and as the abbots of monasteries. Laymen sought these appointments in order to collect the rents from the serfs on ecclesiastical land. Then in the sixteenth century the Reformation and the powerful Polish Catholic Counter-Reformation caught the Orthodox church off guard. Many educated Ruthenians were abandoning their native religion for Calvinism or Roman Catholicism. Desperate for an improvement in their affairs, a number of Orthodox bishops in Ukraine entered into communion with the Pope of Rome. By the terms of the Union of Brest of 1596, the Ruthenian church was allowed to retain its customary practices, such as a married clergy and the use of both wine and leavened bread in the Eucharist. The Ruthenian Orthodox who now recognized the supremacy of the pope of Rome were known as Uniates.

The church union provoked a rebellion among the monastic clergy, who rejected what their bishops had decided. This made trouble enough for the Uniate bishops in Belarus and Ukraine, but much more threatening was the repudiation of the union by the Cossacks. The defense of the ancestral Orthodox faith gave the Cossacks an ideology under whose banner they could rally. Orthodox bishops who refused to embrace the union began to look for an alliance with Muscovy, an Orthodox power that shared certain features of the old Rus’ heritage.

All the tensions – social, ethnic, military, and religious – exploded into war in 1648. An angry Cossack leader, Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, launched a major revolt against the Commonwealth and the nobles. Khmelnytsky was a brilliant commander and a master diplomat. He married his son to a princess of neighboring Moldavia, an Orthodox country. And in 1654 he took the fateful step of entering into alliance with the Tsardom of Muscovy. This was the first time Russia became involved in Ukrainian affairs. It never withdrew.

The war between the Commonwealth and the Cossacks was as bloody as any civil or religious war has ever been. This was an era when wounds were easily infected and impalement a common method of execution. The Jewish inhabitants of Ukraine suffered a particular tragedy during the uprising. The Jews were rarely combatants, but many had been serving as agents of the hated manorial system. Scholars estimate that the Cossacks killed almost half of the Jewish population in the war zone.

War continued for decades thereafter, but the front stabilized in the 1670s and 1680s. The results of the conflagration marked a turning point not only in Ukrainian affairs but in the history of Eastern Europe as a whole. Until Khmelnytsky’s uprising, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the dominant power in Eastern Europe. After the uprising, Muscovy-Russia emerged on top. A century later, Poland-Lithuania ceased to exist, partitioned among Russia, Prussia, and the Habsburg monarchy. Most of the Ukrainian-inhabited territories of the former Commonwealth were taken by Russia, but Galicia was annexed by Austria in 1772 and a part of Moldavia, soon to be known as Bukovina, was annexed shortly thereafter.

Aside from redrawing the map, the Cossack revolt had other consequences for both Ukraine and Russia. The Cossack leaders, now much enriched, endowed churches and monasteries as never before. Particularly generous was Hetman Ivan Mazepa. He funded costly decorations for churches in Ukraine and funded Orthodox projects in other countries, such as the publication of an Arab translation of the New Testament. Mazepa tried to revolt against Tsar Peter I in 1708-09 during the Great Northern War, but he failed and died in exile in Moldavia.

Kyiv had emerged as a center of Orthodox learning already under Polish rule. In 1632 the Orthodox metropolitan of Kyiv, a Moldavian by the name of Petro Mohyla, founded a school of advanced learning that eventually became known as the Kyiv Mohyla Academy. Modelled on Jesuit colleges in Poland, it functioned much like a university. The highly educated churchmen who graduated from the academy served as bishops and teachers throughout Russia, which had nothing remotely equivalent to this institution of higher education. Ethnic Ukrainians dominated ecclesiastical and intellectual life in eighteenth century Russia. Also in Kyiv was the Kyivan Caves Monastery with its own printing press and an influential school of icon-painting. The Ukrainians introduced polyphony into Orthodox music, and Ukrainians staffed the choirs at the court of the tsars and tsarinas.

1783

With its star ascendant in Eastern Europe, Russia expanded west and south. It had already managed to expand east to the Pacific by the middle of the seventeenth century. As has previously been mentioned, Poland-Lithuania was partitioned out of existence at the end of the eighteenth century (1772-95). All of what is today Belarus was joined to Russia. Russia already possessed all Ukrainian territories east of the Dnipro River. But with the partitions of Poland it gained the territories west of the Dnipro up to the river Zbruch, its border with Austria.

In 1783, during the reign of Empress Catherine II, Russia succeeded in conquering and annexing the Crimean Khanate. This put an end to the last traces of the Mongol invasion of Rus’, removed Turkish influence from the steppe, and opened the northern Black Sea coast to development. Many of the Tatars fled to what is today modern Turkey. Catherine invited colonists from abroad to settle in the underpopulated region – Germans, Greeks, Serbs, Bulgarians, and others. She also built new port cities along the coast, notably Odesa and Kherson. Most Ukrainians were enserfed and tied to the land, so originally the south had less of a Ukrainian ethnic presence than other regions of today’s Ukraine.

The disappearance of both Poland-Lithuania and the Crimean Khanate made the Cossacks redundant. They were no longer useful to the Russian state. Emperor Peter I had already restricted the rights of the Cossacks, especially after Hetman Mazepa’s revolt. Peter laid waste to the capital of the Cossacks’ semi-state, known as the Hetmanate. Catherine, like Peter, was a modernizer and aimed at the centralization and unification of her state. Although she was never threatened by a Cossack uprising, as Peter had been, she wanted Ukraine to be ruled like every other part of Russia. She dismantled all the institutions peculiar to the Hetmanate. Earlier, the territorial administration of Ukraine east of the Dnipro River had been divided into Cossack regiments. When Catherine was done, the regiments no longer existed as territorial units; instead the former Hetmanate was divided into three gubernias, just like elsewhere in her empire.

Catherine also formally instituted serfdom, and now former Cossack officers could enserf the local population with the backing of the state. The officers aimed at assimilating into the Russian nobility and sought offices in the new state service. They spoke Ukrainian with their peasants, but among themselves they increasingly spoke and wrote in Russian.

At the end of the eighteenth century, what is today Ukraine was divided as follows. The vast majority of Ukrainian territories had now come under Russian rule. The landowners in Ukraine east of the Dnipro, known as Left-Bank Ukraine, were Russophone Ukrainians or Russians. West of the Dnipro, in Right-Bank Ukraine, the majority of the landownders were Polish. The far west had been taken by the Habsburg monarchy. In Galicia, the landlords were Polish. In Transcarpathia, the elite was Hungarian. In Bukovina, the obligations of serfdom were lighter than anywhere else, and landlords could be Romanians, Greeks, or ethnic Ukrainians. Throughout these territories, the peasantry was enserfed and, for the most part, ethnically Ukrainian.

Ukraine also contained a large Jewish minority, primarily engaged in trade, crafts, and innkeeping. Before the partitions of Poland, the Russian state did not allow Jews to settle on its territory. The Cossacks of the Hetmanate had petitioned several times to allow Jews to enter their territory, since before the uprising they had often relied on the services of Jewish merchants. The Russian emperors and empresses would not agree. However, when Catherine took Right-Bank Ukraine and Belarus from Poland, she stood before the choice of either expelling tens of thousands of Jews or making some kind of compromise. She chose the latter. Jews were allowed to enter Russia, but they were restricted to certain territories, including Ukraine. This was the Pale of Settlement. Roughly speaking, Jews made up about 12 percent of the population in the Right Bank and about 5 percent in the Left Bank; the south, the territory of the former Crimean Khanate, attracted many Jewish settlers, especialy merchants drawn to the large trading centers of Odesa and Kherson. In Galicia, over 10 percent of the population was also Jewish.

1861

In 1861 serfs in the Russian empire were emancipated. In many ways it was similar to the emancipation of the slaves in the USA two years later. It meant that the legal bonds of servitude were broken, but it did not mean that either the serfs or the slaves achieved meaningful equality. They remained at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy as well as of the cultural and educational hierarchy, and they had little or no political influence.

The first Ukrainian serfs to be emancipated were not those who lived in Russia, but the peasants who lived in the Habsburg monarchy. They were emancipated already in 1848, as one of the results of the otherwise defeated revolution of 1848 that had encompassed almost all of Europe. The plots that peasants had farmed for their own subsistance now became their legal property. Woods and forests – the commons – were divided between peasant communities and the lords, with the latter being favored in the division.

The terms of emancipation were less favorable in Russia, and the peasants were saddled with a heavy debt to indemnify their former owners for the loss of their labor and taxes.

Eighteen sixty-one was also the year that the national bard of Ukraine, Taras Shevchenko, passed away. He had been born a serf, but his master noticed his talent as an artist and paid for painting lessons. In 1838 a group of artists and collectors raised the funds necessary to buy his freedom, allowing him to study at the prestigious Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. Yet Shevchenko’s legacy as a painter was soon eclipsed by his reputation as a poet. He published his first book of poetry in 1840, the Kobzar (Minstrel). These and subsequent poems electrified educated Ukrainian circles. They expressed the raw emotions of the serf class and of the nation emerging from it. Shevchenko was celebrated all over Ukraine, a frequent guest in the gentry’s salons. He fell in with a group of radical Ukrainian intellectuals who dreamed of emancipating the serfs and replacing the centralized Russian autocracy with a federative democracy. This led to his arrest in 1847 and exile to a penal colony in Kazakhstan. He was allowed to return to Ukraine in 1859, but died before two years had passed, at the age of forty-seven.

This was only one of the many interesting and illustrious figures who contributed to the Ukrainian national revival of the nineteenth century. Rather than listing other prominent representatives, we offer instead a sketch of the process of the national awakening.

Ukrainians were a stateless people, hardly known outside Eastern Europe. Like many other stateless peoples, such as the Slovaks and Latvians or Scots and Welsh , they underwent a national awakening inspired by Enlightenment ideals. Educated members of these peoples, generally a rather thin stratum, began to collect the songs and stories of the common folk, to examine their fashions and write down their dialects. On the basis of this work, the intelligentsia began to compile dictionaries, forge a literary language, and define national costumes, dances, and musical instruments. The awakeners rifled through archival documents to construct a narrative of the past, a history, for their peoples, typically finding that their unknown nation dated back at least a millennium. These processes were common throughout Central and Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century, and the intellectual-cultural work grew ever more sophisticated as the century progressed. Soon organizations and political movements developed. And as faith in the old imperial order was crumbling around the turn of the twentieth century, these emerging nations began to dream of independent statehood.

Unlike most of the peoples undergoing this process, the Ukrainians were not concentrated in a single state, but were divided between the Russian empire, where most Ukrainians lived, and the Habsburg monarchy. In Imperial Russia the Ukrainian movement was initiated by the offspring of the Cossack officer class. A primary center was in Kharkiv, where a university had been founded in 1805. Periodicals out of Kharkiv, like The Ukrainian Herald and The Ukrainian Journal, promoted Cossack history and popularized the term “Ukraine,” which had been used by Khmelnytsky earlier. A university was also founded in Kyiv in 1834, and this city emerged as the center of the Ukrainian movement as of the 1840s. But the movement’s development in Russia was severely handicapped. Publication in the Ukrainian language was restricted, nearly banned, by decrees of 1863 and 1876. Leaders of the movement were arrested or forced into exile. The tsarist regime did not develop a comprehensive system of primary education, and the schools that existed were prohibited from using the Ukrainian language in the classroom. These circumstances, combined with the lack of basic civil rights in Russia, such as freedom of the press and freedom of association, prevented the Ukrainian movement from making much of an impact on the vast majority of ethnic Ukrainians, namely the peasants. In Russia, the Ukrainian movement was top heavy, composed of outstanding visionary intellectuals who lacked a social base. The first Ukrainian political party in the empire was the underground Revolutionary Ukrainian Party, founded in 1900. Like the movement that produced it, it combined social justice concerns with national goals. It also issued a brochure calling for an independent Ukraine.

Three Ukrainian-inhabited regions existed in the Habsburg monarchy: formerly Polish Galicia, formerly Moldavian Bukovina, and Transcarpathia, which had been part of Hungary since about 900. The awakener stratum here was not of Cossack origin, but clerical. Galicia and Transcarpathia had accepted the Uniate faith in the late seventeenth century. (Uniatism disappeared completely from the Russian empire by the mid-1870s.) The enlightened Habsburg empress Maria Theresa made a number of improvements in the affairs of the Ukrainian population. Symbolically, she renamed the Uniate church the Greek Catholic rite to emphasize its parity, in her eyes, with the Roman Catholic rite. She also instituted higher education for the Greek Catholic parish clergy, who had not been provisioned with such before. Eventually, Greek Catholic seminarians were to study at Lviv University, which had been originally founded in 1661. These educated priests, and later their sons, served as the awakeners and leaders of the national movement in the monarchy. The Ukrainians of all social classes here called themselves Rusyns (or Ruthenians) rather than Ukrainian. The latter name did not become dominant in these western regions until about 1900.

The European revolution of 1848 first brought the Ruthenians into politics and saw the appearance of the first newspaper in a variety of the Ruthenian language. There were arguments for many decades about what language the Galician Rusyns should write in – in local dialects mixed with Church Slavonic or in Russian or in the Ukrainian literary language that had developed among the Ukrainian intelligentsia of the Russian empire. The debate over language was a debate also over identity. Were they simply Rusyns or a branch of the Russian nation or a branch of the Ukrainian nation? The Galicians and, with somewhat of a lag, the Bukovinians opted for Ukrainian identity by the end of the century, while the Ruthenians in Transcarpathia remained divided. When Austria introduced a constitution, a limited suffrage, and civil freedoms in 1867, the fortunes of the Ukrainian movement in Galicia rose rapidly. Numerous periodicals appeared and created the “imagined community” of a nation across villages and towns. Public primary education was introduced in 1869 and the language of instruction in eastern Galicia, where the Ruthenians lived, was Ukrainian. The intelligentsia in Lviv and the network of clergy in the countryside founded numerous organizations for the peasantry – choirs, fire brigades, cooperatives, and adult education societies. The first Ukrainian political party in Austria was founded in 1890, the agrarian socialist Radical Party. By the late 1890s young Radicals were formulating a program calling for an independent Ukrainian state. Also, members of the Radical Party broke off to form the Ukrainian National Democratic Party, a left-liberal party that would dominate Galician-Ukrainian politics until 1939, and the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, a workers’ party linked with the Austromarxists. In the early 1900s all these parties supported a series of agricultural strikes, seeking to raise the wages of the poorest Ukrainian peasants. The mood in late-nineteenth century Galicia was well captured by the poet Ivan Franko: “I am a son of the people, the son of a nation on the rise. I am a peasant: prologue, not epilogue.”

1917

By the eve of World War I, mighty changes were brewing in the Russian empire. In 1905 the First Russian Revolution broke out. New political parties emerged from the shell of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party – two Ukrainian Social Democratic parties and the more nationalistic Ukrainian People’s Party. The tsarist autocracy was forced to make a number of liberal concessions, including the right to publish in the Ukrainian language. Many Ukrainian newspapers and journals appeared overnight as did Ukrainian civic organizations. Russian imperial society was deeply polarized between reaction and revolution. Ukrainians, like other groups that were discriminated against under tsarism, such as the Jews, sided with the revolution. But the tsar and forces of reaction were able to push back against the liberal concessions that had been made, so that the Ukrainian movement was not able to make the kind of progress it would have had Russia evolved toward democracy instead.

And even this relatively liberal period in the history of Russia was cut short by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The front moved back and forth across Ukraine: in 1915 the Russians were in Lviv and in 1918 the Germans were in Kyiv. This new industrial war took many lives and devastated the infrastructure across Ukrainian territories.

Russia was in many ways the weakest of the powers engaged in the war. It lagged behind the rest of Europe in industrial development, it was plagued with social tensions, and its soldiery was the least educated of any of the fighting forces. The strain on the population led to spontaneous outbreaks of protest, ultimately forcing the tsar to abdicate in March 1917.

The revolution gave newfound life to the Ukrainian movement. As councils or soviets popped up all over Russia, Ukrainians in Kyiv founded their own, the Ukrainian Central Rada. (Rada in Ukrainian is the equivalent of soviet.) The Rada, the Ukrainian revolutionary parliament, was dominated by social democrats and peasant-oriented socialist revolutionaries. It sought recognition and autonomy from the Provisional Government, which claimed to be in charge of all of Russia. At one point in this struggle, the Rada proclaimed the existence of the Ukrainian People’s Republic; this was not envisioned as a totally independent state, but part of a democratic Russian federation. But while the Rada was tussling with the Provisional Government, the latter was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in November 1917. The Rada considered the Bolsheviks to be extremists creating chaos in the former empire, and the Bolsheviks considered the Rada to be petty bourgeois and nationalist.

In December 1917 the Bolsheviks attacked the Rada militarily. The forces of the Ukrainian People’s Republic were not able to defend their territory, and the Rada called upon the Germans to rescue them. World War I was still proceeding, and the Germans looked to Ukraine as a source of food and raw materials and as a buffer state against Russia, with whom they were still at war. German expropriations led to peasant revolts. After the Germans’ defeat by the Entente and their withdrawal from Ukraine, things became ever more complicated. The Ukrainian forces fought the Bolsheviks as well as the White Russian generals of the civil war. They met with little success. The army, headed by Symon Petliura, was undisciplined, and units associated with it engaged in bloody pogroms against the Jewish population, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths. New forces kept entering the fray – warlords, the most famous of whom was the anarchist Nestor Makhno; a French expeditionary force; and the Polish army under the leadership of Józef Piłsudski. The Ukrainian Galician Army also joined Petliura’s forces in summer 1919; these were disciplined, experienced soldiers, but they could do little to improve Ukrainians’ fortunes.

The Ukrainian Galician Army had been the armed force of the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic. That republic had been proclaimed in Lviv on 1 November 1918, as Austria-Hungary was collapsing under the impact of defeat in war. The Ukrainians lost Lviv in a matter of weeks, since – as in most cities on Ukrainian territories – only a minority of its inhabitants were ethnically Ukrainian. The Poles in the city succeeded in forcing the Ukrainian government out. The Jewish population tried to remain neutral during the conflict in Lviv, but the Poles suspected them of favoring the Ukrainians. As a result, Polish soldiers and the urban crowd unleashed a pogrom. The Ukrainian People’s Republic was not yet defeated and held most of eastern Galicia until June 1919. They were only forced to leave these territories when a Polish army, equipped and trained by the French to fight against the Bolsheviks, overwhelmed them. That is how and why the Ukrainian Galician Army joined with Petliura’s forces to the east.

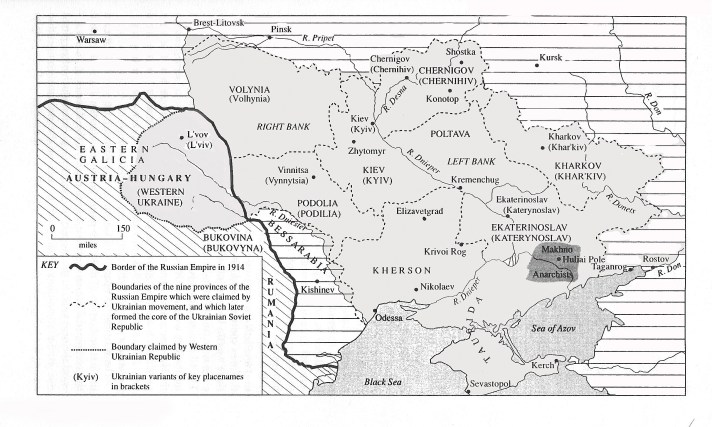

Ukraine experienced six terrible years of war and civil war before things settled down. In the early 1920s, the territory of what is today modern Ukraine was divided among a number of states. Most of Ukraine became the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Crimea, however, was part of Soviet Russia. Since Hungary was defeated in the war and stripped of most of its historical territories, Transcarpathia was assigned to the newly created state of Czechoslovakia. Bukovina was incorporated into Romania. And Galicia, which had been part of Austria, as well as Volhynia, which was just to the north of it and had been part of Russia, were incorporated into the new Polish state. The failure to establish theor own state, at a time when long-dead states such as Poland and Lithuania were resurrected and entirely new states such as Finland and Czechslovakia were created, was to be a source of great bitterness and frustration for Ukrainians.

The only flicker of a candle in the national darkness was Soviet Ukraine. In Lenin’s view, the Ukrainian forces may have been defeated, but not the Ukrainians’ national aspirations. He therefore, against the will of many other leading Bolsheviks, insisted on the creation of a Ukrainian Soviet republic, roughly in the borders that had been claimed by the Central Rada. In line with Lenin’s policies, the Bolsheviks in 1923 adopted a policy of indigenization (korenizatsiia) in the non-Russian Soviet republics. This policy resulted in an unprecedented blossoming of Ukrainian culture. During ukrainization, as the indigenization policy was known in Soviet Ukraine, Ukrainians devised a unique educational system; produced avantgarde cinema, theater, literature, and visual art; and undertook extensive research on Ukrainian history and culture. This was the era of Ukrainian national communism, when ethnic Ukrainians were appointed to leading positions in the political and economic apparatus. Ukrainians from Poland, who were discriminated against, migrated to Soviet Ukraine to work in encyclopedia projects and many other cultural endeavors.

In Poland, the Ukrainian educational system that had existed under old Austria was dismantled. Ukrainians were not hired for state jobs, such as in the railways or local administration. They began to develop a state within a state, funding private Ukrainian educational opportunities and cultural work with funds provided by the Ukrainian cooperative movement. The Greek Catholic church founded a theological academy which actually trained numerous secular intellectuals, since access to university education was limited for Ukrainians, as it was for Jews, in interwar Poland. The catalogue of Poland’s discriminatory policies against national minorities is long.

Politically, the dominant party was the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance, whose name accurately reflected its politics. There were also left-wing parties, ranging from the fairly moderate Ukrainian Radical Party to the Communist Party of Western Ukraine. In between were the Social Democrats, some of whom were pro-Bolshevik. In the 1920s pro-Soviet attitudes were widespread in Galicia because of what was happening in national communist Soviet Ukraine. There was also a strong women’s movement allied with the National Democrats.

On the right of the political spectrum was the Ukrainian Military Organization, known by its Ukrainian initials UVO. It continued a struggle against Polish rule from the underground, robbing post offices and engaging in other forms of terrorism. In 1929 many in UVO joined the newly founded Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). OUN also engaged in robberies and assassinations. During their summer vacation in 1930 the youth of OUN and UVO launched a campaign of arson against Polish estates and undertook other forms of sabotage. The Polish government responded with a vicious pacification of the Ukrainian countryside, beating Ukrainian activists of all political stripes and destroying buildings belonging to the Ukrainian movement. It was a brutal overreaction, and Ukrainians at home and in North America called upon the international community to condemn Poland.

1933

In 1933 the policy of ukrainization was officially ended in Soviet Ukraine. But before that, in 1930, numerous Ukrainian cultural and academic workers were arrested and put on trial for belonging to a fictitious Union for the Liberation of Ukraine. Vicious purges of the Ukrainian intellectual elite marked the entire 1930s. Few survived. In 1933 the minister of education in Soviet Ukraine, Mykola Skrypnyk, and the proletarian writer Mykola Khvyliovy committed suicide in protest.

Aside from the Stalinist terror, Ukraine suffered immensely from forced collectivization. The planning and implementation of collectivization were abysmally poor, and food shortages haunted the entire USSR. Famine broke out in Kazakhstan, the Volga region, and Ukraine. The manmade famine in Ukraine, the height of which came in 1933, took 4 million lives out of a total population of about 31.5 million. The effects of the collectivization famine were most intense in Ukraine. Numerous witnesses related that even small amounts of food were taken from individual households, leaving the inhabitants to starve. Because the famine occurred at the same time as Stalin was also persecuting the Ukrainian elite, which he considered disloyal, the deadly effects of food shortages throughout the USSR were disproportionately displaced to Ukraine.

The purges and famine in Soviet Ukraine put an end to all pro-Soviet sympathies in the western Ukrainian regions outside Stalin’s reach.

Most of Europe in the 1930s was polarized between left and right, between the communists and the fascists. Street fights between left and right paramilitaries broke out in Vienna, and Spain, of course, was plunged into civil war. Democracy on the continent was weak. In 1933 Hitler came to power in Germany. He made no secret of his hatred for Jews and his plans to undo the terms of the peace settlement imposed on Germany after defeat in World War I. In his book Mein Kampf Hitler developed his racist visions and announced for all the world to read his intent to seek Lebensraum (living space) for Germans by invading the Soviet state.

Hitler exercized a baleful influence on the Ukrainian right in Poland, particularly on OUN. The Nationalists had already been spying for and accepting aid from Germany before the Nazis took it over. But now the Nationalists’ orientation on Germany became stronger. Hitler was the enemy of their enemies, the Soviet Union and Poland. Hitler was revising the same Versailles settlement that had left Ukrainians stateless. He was uniting the German people that had previously lived in different states: he annexed Austria in March 1938 and the so-called Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia in October of that year. As a result of the latter annexation, what had been Czechoslovakia began to break down into separate units. One of these was Carpatho-Ukraine, formed from some of the Rusyn/Ukrainian-inhabited territory of Czechoslovakia. Ukrainians outside the Soviet Union, in Galicia and North America, were ecstatic about the formation of this statelet. OUN sent its militants to Carpatho-Ukraine to influence its administration and to join its nascent armed force. When Hungary attacked and put an end to Carpatho-Ukraine in mid-March 1939, some leading cadres of OUN perished in the struggle for Carpatho-Ukraine’s independence. There was some ideological overlap between OUN and German national socialism from the beginning, and as the 1930s progressed the Nazis’ influence on Nationalist ideology increased. Particularly noticeable was the growth of antisemitism in OUN during the latter 1930s.

1939

World War II broke out on 1 September 1939. Shortly before this, Germany and the Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact. A secret codicil of the pact was a division of Eastern Europe between the two powerful dictatorships. On 17 September the Soviets invaded Western Ukraine, i.e., Galicia and Volhynia in Poland, and in a matter of weeks annexed it to the Soviet Union. The twenty-one months that the Soviets occupied Western Ukraine were brutal. Hundreds of thousands of people were deported to the Arctic, Kazakhstan, and Siberia. At first the Soviets arrested and deported the Polish elite of Eastern Poland/Western Ukraine. They also dispatched to the Gulag Jews who fled from the German zone of Poland to the Soviet zone. And near the end of the occupation, the prisons were filled with Ukrainians. The Soviets also took Bukovina from Romania in June 1940, subjecting it to the same type of regime.

During the Soviet occupation, life changed dramatically. What was once a diverse array of periodicals and newspapers was now replaced by repetitive mouthpieces of the new authorities. Basic provisions disappeared from the stores. Stores and businesses were nationalized. All the basic civil rights that had existed even under authoritarian Poland were swept away. Fear pervaded the population, as at any moment literally anyone could end up on a freight car to Siberia. All the preexisting Ukrainian political parties dissolved themselves soon after the Soviets took power. They were never to revive their activities. The Soviets hunted down and executed dissident communists in Western Ukraine, national communists and left communists. There was only one Ukrainian political movement that managed to survive the Soviet period – OUN. It had experience in conspiratorial activity, and – despite arrests and executions at the hands of the authorities – managed to double its membership. In June 1941, the organization had about twenty thousand members and thirty thousand sympathizers. If years of underground experience allowed OUN to survive, the repressive Soviet system drove some Ukrainians, especially youth, into its ranks.

On 22 June 1941, Hitler launched his ill-fated invasion of the Soviet Union. In the days before the Germans were able to reach Western Ukraine, the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, arrested thousands of suspected Ukrainian Nationalists, lest they aid the enemy. Then, since the German advance was so rapid, they were unable to evacuate the prisoners to the east. Instead, they executed them en masse, killing about fifteen thousand in Western Ukraine, mainly Ukrainians, but also Poles and Jews. These NKVD murders enraged the population of Western Ukraine, raising emotions to a very high pitch. When the Germans arrived, Jews were forced to retrieve the victims’ bodies from the prisons and lay them out in the courtyards for people to find their relatives. Parts of the city of Lviv stunk from the decomposing bodies. A pogrom broke out in which the Ukrainian National Militia of OUN played a major role, although the German SS was responsible for executing most of the hundreds of victims.

Violence against Jews continued throughout the war. About 1.5 million Jews were killed on the territory of today’s Ukraine, accounting for about a quarter of the victims of the Holocaust. Most Jews died not far from where they had lived, shot on the edge of ravines or pits dug for the purpose. The shooters were primarily special SS units, the Einsatzgruppen, aided, however, by the collaborationist police.

Nazi policy towards the local non-Jewish population was also harsh, though it stopped short of systematic mass murder. Over three million Soviet prisoners of war died in German camps from exposure and starvation. Over two million young Ukrainians were deported to Germany as slave laborers (Ostarbeiter). In much of Ukraine, the Germans rounded up youth as they came out of church or a dance and packed them on to trains.

What is today Ukraine was divided among a number of different administrations during the war. Galicia was incorporated into the rump Poland, the General Government, as Distrikt Galizien. Bukovina and neighboring regions were reannexed by Romania, which also took the Odesa region and called it Transnistria. Hungary held Transcarpathia/Carpatho-Ukraine. Parts of Ukraine were under direct German military rule. The largest part of dismembered Ukraine was the Reichskommissariat Ukraine.

The most savage of these administrations was the Reichskommissariat, which had its capital in Rivne in Volhynia. Although OUN had been cooperating with the Nazi occupation as policemen in Volhynia, it realized that the population was fed up with German rule and engaging in spontaneous acts of resistance. Rather than let the anti-German sentiments feed into support for the Red partisans who were coming through the forests, OUN launched its own anti-German insurgency in the spring of 1943. It was a limited resistance movement, since OUN did not want a Soviet victory either. OUN’s armed force, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), ambushed German patrols and interfered with round ups for slave labor, but it did not try to derail German trains carrying supplies to the front. They preferred that the Germans and Soviets pummel each other. The UPA resistance did not do anything to protect the Jewish population hiding in the woods of Volhynia; in fact, it issued an order to kill all Jews and any Ukrainians who hid them. UPA also began to ethnically cleanse Volhynia, and afterwards Galicia, of its Polish population. Historians estimate that UPA killed about sixty thousand Poles, for the most part civilians.

The war in Ukraine was extremely brutal. In Eastern Europe the conflict was not between the Western Allies and the Germans but between the Soviets and the Germans, i.e. between two lethal regimes. People had to make choices. Generally, the population of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine tended to look at the advancing Red Army as liberators. But this was much less the case in Distrikt Galizien in Western Ukraine. The experience of Soviet rule in 1939-41 hardened attitudes. Also, German rule here was much more favorable to Ukrainians than anywhere else on Ukrainian-inhabited territory. The Germans used the Ukrainians as a counterweight to the Poles and relied on Ukrainian Nationalists to help set up the civil administration and police. Recruitment of slave labor also existed here, but there were certain mitigating factors that did not obtain elsewhere. Educational opportunities for Ukrainians existed in Distrikt Galizien that had no equivalent in the Reichskommissariat. Because of Nationalist influence, the Ukrainians of Galicia were less horrified by the murder of the Jewish population than were Ukrainians in the Reichskommissariat. In fact, the liquidation of the Jewish population proved to be an economic boon for the Ukrainian cooperative movement during the war. The Germans had enough popularity in Galicia in mid-1943 and 1944 that eighty thousand Ukrainians volunteered for a Waffen-SS unit, the Division Galizien. Only a portion of these volunteers actually ended up fighting. Waffen-SS Division Galizien played a very minor role in anti-Jewish and anti-Polish actions, but it collaborated in quelling the antifascist Slovak National Uprising in 1944.

After the Soviet reconquista of Western Ukraine, UPA ignited an anti-Soviet insurgency, which lasted into the late 1940s. The Soviet counter-insurgency was ruthless. Dead UPA soldiers were lined up against the fence in villages, so that relatives could identify them. If anyone did admit to finding their son or brother among the dead, they would be arrested and sent to labor camps. Hundreds of thousands of Western Ukrainians were deported as part of the counter-insurgency and in connection with the collectivization drive.

A result of this history, which was to play a role in the memory politics of independent Ukraine, was that Galician Ukrainians remembered the Soviets as worse than the Germans, while in the rest of Ukraine the tendency was rather the other way around.

One result of the war for all of Eastern Europe was that states became ethnically more homogenous. The Germans had killed most of the Jews. All East European countries expelled their ethnic German population. In Ukraine, the Polish population largely disappeared. Many had been killed in the Stalinist purges of the 1930; large numbers of them were deported from Western Ukraine in 1939-41; the UPA ethnic cleansing campaign eliminated tens of thousands more in 1943-4; and after the war, the Soviets organized population exchanges with Poland, trading surviving Poles for Ukrainians who had ended up within the new People’s Poland. Jews who managed to survive the war generally left Western Ukraine for Poland, and then for Israel and America. The former Jewish population of Ukraine, with its religious traditions and its Yiddish language, existed no more. Such Jews as remained in Ukraine were indistinguishable from other Soviet citizens. Russian replaced Yiddish.

The absence of Poles and Jews opened up many towns and cities in Western Ukraine for ethnic Ukrainian migrants. This was a major social advance for the Western Ukrainian population, although they had to compete with incoming Russians and Russophone Ukrainians from the East. The latter formed the political elite throughout Ukraine.

After Stalin died, the Soviet Union became a much safer place to live. Many of the Western Ukrainians in the Gulag were amnestied and returned home. There were brief moments of thaw in regard to Ukrainian culture, all concentrated in the period 1956-72. Otherwise, the postwar period in Soviet Ukraine witnessed relentless russification. Those who objected were arrested and imprisoned or exiled. These were the dissidents, and they represented various shades of political opinion, from Marxists like Ivan Dziuba and Leonid Pliushch to Nationalists like Valentyn Moroz and Ivan Kandyba. Composers, poets, and artists were also associated with the dissident milieu.

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic that emerged from the war encompassed not only the old, pre-1939 Soviet Ukraine but the territories Stalin took in 1939-41, i.e., Galicia (basically Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Ternopil oblasts), Volhynia (basically Rivne and Volhynia oblasts), and Bukovina (basically Chernivtsi oblast). In addition, Soviet Ukraine added Transcarpathia oblast in 1945, when it was ceded by Czechoslovakia. (The twenty-four oblasts of Ukraine are the equivalent of states or provinces.) The last addition to Soviet Ukrainian territory was Crimea, transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954. The year 1954 was the three-hundredth anniversary of the Treaty of Pereiaslav, by which Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky placed Ukraine under the protection of the Russian tsar.

1991

The 1970s and first half of the 1980s in the Soviet Union have been called “the period of stagnation.” The USSR was plagued with an aging and unwell leadership. General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev had been born in 1906. A heavy smoker and drinker, his health declined dramatically by the mid-1970s. After his death in 1982, he was succeeded by two more elderly general secretaries, both of whom were dead by spring 1985. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union then chose a younger man as general secretary, Mikhail Gorbachev, hoping he would breathe new life into the party and the country. Gorbachev promised liberal reforms, whose slogans were perestroika (reconstruction) and glasnost’ (openness). The reforms he initiated were eventually to lead to the end of communism in Europe and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The reforms reached Kyiv more slowly than in other major Soviet centers. The head of the Ukrainian communist party, Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, was a fossil of the stagnation period. He came to power in 1972, inaugurating his tenure as Soviet Ukraine’s first secretary by a massive arrest of dissidents and a clampdown on Ukrainian culture and scholarship. He kept a tight grip on Ukraine as long as he could. In 1986 an explosion occurred at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant, the worst nuclear accident in history. Shcherbytsky tried to hush it up and did not even cancel the Mayday parade in Kyiv that took place only five days later. His handling of this crisis provoked denunciations at the June 1986 conference of the Ukrainian Writers’ Union. Ivan Drach, whose son was sent to clean up at Chornobyl and was poisoned by radiation, was particularly outspoken. Writers at the congress also called for more Ukrainian cultural autonomy.

Changes in Ukraine began to accelerate after numerous dissidents were released by the all-Union government from prison and exile and returned to Kyiv and Lviv in 1988-89. In early 1989 the dissidents now at liberty joined with the writers to form a movement to press for Ukrainian rights. It was called the People’s Movement of Ukraine for Reconstruction, popularly known as Rukh. Rukh issued a democratic program advocating a civic Ukrainian nation, i.e., one not limited to ethnic Ukrainians or Ukrainian-speakers but comprising all inhabitants of the Ukrainian republic. Before long it was advocating the independence of Ukraine from the Soviet Union.

Strivings for independence on the part of the Ukrainian public came at a propitious moment. Just then, a new figure was coming to prominence, Boris Yeltsin. He challenged Gorbachev, who was becoming more conservative in reaction to the forces his reforms had unleashed, not just in Ukraine but in Lithuania, Armenia, and other republics. Gorbachev wanted to preserve the unity of the Soviet Union. Yeltsin attacked Gorbachev not from the all-Union level, but from the level of the Russian republic. He became chair of the Russian Supreme Soviet in 1990, which signified he was head of state in Russia. He made alliances with the republican level of leadership outside Russia, and in particular with the communists of the Ukrainian republic. Yeltsin pushed through a declaration of sovereignty for Russia on 12 June 1990, and Ukraine followed suit on 16 July. The declaration of state sovereignty of Ukraine was so far-reaching that when Ukraine actually became independent, on 24 August 1991, the declaration of independence was less than one hundred words long and contented itself with proclaiming it was fulfilling the terms of the sovereignty declaration. Ukraine’s equivalent of Yeltsin was Leonid Kravchuk; a week after the promulgation of sovereignty he was elected chair of Ukraine’s Supreme Soviet, better known by its Ukrainian name – the Verkhovna Rada. Kravchuk developed good relations with Rukh and also with Yeltsin. Both communist leaders wanted to dissolve the Soviet Union, and they realized their goal in December 1991.

The declaration of independence was preceded by a clumsy coup attempt by Kremlin hard-liners on 19-23 August 1991. Yeltsin became a hero in Russia for opposing the coup. Ukrainian communists were not sure what to do, but the day after the coup failed, the Verkhovna Rada declared independence. Independence was to be confirmed by a referendum of the population of Ukraine. It took place on 1 December and resulted in a majority vote for independence. However, it was not entirely like the elections Ukraine was to have later. Soviet-style practices were still in evidence, with some electoral districts reporting that 99.9 or 100 percent of the eligible voters took part, of whom over 97 percent were in favor of independence. Nonetheless, the referendum dotted the “i” on the word independence.

On the same day as the referendum Ukraine held its first presidential election. Kravchuk won handily, with over 60 percent of the vote. Already in evidence was the regional voting pattern that marked almost every election in independent Ukraine: the West voted one way, the South and East another way.

Concretely, Kravchuk in 1991 won every oblast in Ukraine except for the three Galician oblasts. In the 1994 elections the western half of the country voted unsuccessfully to reelect Kravchuk, but the rest of the country voted for Leonid Kuchma from Dnipro (at that time Dnipropetrovsk) in south-central Ukraine. In 1999 Kuchma ran against the communist Petro Symonenko. The three Galician oblasts voted over 90 percent in favor of Kuchma, while Symonenko did well in northcentral Ukraine, Donetsk and Kherson oblasts, and Crimea. In the 2004 elections, which sparked the Orange Revolution, former head of the national bank and prime minister Viktor Yushchenko won, taking the entirety of West and Central Ukraine. His opponent Viktor Yanukovych of Donetsk took the South and East. In the next election, Yanukovych won against former prime minister Yuliia Tymoshenko. Yanukovych again took the South and East.

This voting pattern reflected different historical experiences that led to different attitudes toward Ukrainian ethnonationalism and toward Russians. The West was solidly in the nationalist camp, which soon captured the Center as well. The largely Russophone East and South was less anti-Russian. Galician Ukrainians and Ukrainians from Donetsk or Odesa were only slowly building their solidarity.

The 1990s were very hard on the Ukrainian population. Inflation reached unheard of heights. One’s life savings in rubles might only be worth enough to buy a pack of matches. Where possible, many urban Ukrainians went to their families in the countryside to help on the farms and bring home a bag of potatoes. But some people became very rich as they privatized what had been state property. Common schemes in the 1990s included paying people Soviet wages and selling their products to Europe at Western prices; taking loans from the banks in Ukrainian currency, changing them into American dollars, and somewhat later paying the loans back in devalued Ukrainian currency; stripping existing state enterprises of their assets and selling them; and clear-cutting forests and selling the lumber abroad for hard currency. As a result of the latter practice, Transcarpathia was wracked by floods. Racketeers collected protection payments from nascent retail businesses. Business and organized crime were often indistinguishable There arose in Ukraine a stratum of very rich and powerful businessmen, usually called the oligarchs. Prominent among them were Viktor Pinchuk and Rinat Akhmetov. Such figures retain great influence behind the scenes in Ukrainian politics. The economic crisis of the 1990s began to abate after autumn 1996 when the currency was reformed and the hryvnia introduced to replace earlier forms of Ukrainian currency.

It is important to mention something that did not happen. Although Romania, the former Soviet republics on the Baltic, and other countries of postcommunist Eastern Europe were taken into the European Union in the 2000s, Ukraine was excluded. Things could have turned out quite differently if it had been otherwise.

2014

There was a prelude to the 2014 events, namely the Orange Revolution. The 2004 election was contested, as already mentioned, between two Viktors, Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych. The latter, who was prime minister at the time, had the support of the Ukrainian government and was also the candidate favored by Russian President Vladimir Putin. Yushchenko, an opposition leader, was considered a pro-Western candidate. Yanukovych won the run-off election between the two, by a fairly narrow margin (49.5 percent to 46.6 percent). Yushchenko’s supporters claimed that the election results had been falsified, and a large crowd from all over Ukraine occupied Independence Square, known as Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Ukrainian. Perhaps half a million protesters gathered on the Maidan, in the heart of downtown Kyiv. A stage was erected on the square, and opposition figures gave speeches and popular rock groups played music. Kyivans brought food to the protesters. Western media and politicians also supported the demonstrators and their Orange Revolution. Under pressure from the crowd, a new run-off election was held, but this time observers from other countries were stationed at polling booths to make sure that the voting was fair. When the votes were tallied, Yushchenko proved to be the victor (52.0 percent to 44.2 percent).

Yushchenko was not an effective president, and his term was marked by quarrels with other politicians who had gained prominence during the Orange Revolution, notably Yuliia Tymoshenko. In 2008 Yushchenko even appointed his former electoral opponent, Yanukovych, as prime minister. The major innovations of his term as president were in the realm of memory politics. Unlike any Ukrainian president before him, he initiated not only the rehabilitation of OUN and UPA, but their glorification. He posthumously awarded their leaders, particularly Roman Shukhevych (Supreme Commander of UPA) and Stepan Bandera (head of the largest faction of OUN), the honor of Hero of Ukraine. He also led a massive campaign to have the manmade famine of 1932-33, the Holodomor, recognized by all other countries as a genocide directed against the Ukrainian people. He ordered the collection of over two hundred thousand testimonies about the famine and founded a memorial museum in Kyiv to commemorate the victims.

Yushchenko did not even make it to the run off in the presidential elections of 2010. Instead, Tymoshenko faced off with Yanukovych, who won, 49.0 percent to 45.5 percent.

The victory of Yanukovych was a victory for his clan in Donetsk, who occupied influential positions in his government. He made an about-face from Yushchenko’s nationalist politics, and his minister of education and science, Dmytro Tabachnyk, alienated many Ukrainian intellectuals. Yanukovych was also the most corrupt of the Ukrainian presidents. He and his cronies embezzled in an ostentatious manner. Yanukovych remained popular in his base in the Donbas, but much of Ukraine felt he was a disgrace to the presidency.

The writing on the wall appeared in November 2013. Yanukovych was supposed to sign a political association and free trade agreement with the European Union but instead accepted financial aid from Russia. Once again, the Maidan began to fill with protesters, eventually half a million of them. They were a mixed bunch. Although the Galicians were disproportionately represented, protesters came from all parts of Ukraine. Some were pro-Western democrats, some were far-right nationalists; feminists, members of the LGBT community, anarchists, and socialists were also there. Yanukovych’s government reacted with lethal violence against the protesters, and the nationalists – led by Right Sector – fought back. Over a hundred protesters were murdered by police snipers, and thirteen policemen were killed. By late February 2014, the armed protesters turned the tide, and Yanukovych fled Ukraine for Russia. These events are generally known as the Euromaidan and the Revolution of Dignity.

However, Putin called these events a “fascist coup” and began an invasion of Ukraine. The Ukrainian army had been neglected and was more a source of corrupt enrichment for officers than a fighting force. Russia marched into Crimea unopposed and annexed it. In the course of the invasion most of Ukraine’s navy deserted to the Russians. Crimea was low-hanging fruit. According to the 2001 census, two-thirds of its population was ethnically Russian and only a quarter Ukrainian. Over 80 percent was Russophone. There were more Crimean-Tatar-speakers in Crimea than Ukrainian-speakers. The Crimean authorities had held referendums in the early 1990s to press for independence or at least expand their autonomy, but Kyiv quashed these efforts. After Russia took Crimea in 2014, it held its own referendum on 28 February. It was definitely a Soviet-style election, with 97 percent of voters in favor of joining the Russian Federation.

At the same time, Russia encouraged anti-Maidan, pro-Russian unrest across the East and South of Ukraine, from Kharkiv in the northeast to Odesa in the southwest. Putin called this large swath of Ukraine “Novorossiia,” a reference to a territorial unit carved out of the Crimean Khanate in 1764. The wave of pro-Russian protests, which often involved seizure of government buildings, was called “the Russian Spring.” Owing to timely preventive measures by the hastily reconstituted Ukrainian government, the pro-Russian separatist movements only succeeded in the eastern Donbas region. Two cities – Donetsk and Luhansk – became the capitals of tiny separatist republics. But the battle over the eastern Donbas raged for another eight years, claiming about fifteen thousand lives. The two republics were first governed by rather thuggish military types, but later Russia installed leaders whom they controlled directly. Shelling from the Ukrainian side destroyed many buildings. The “success” of the Russian Spring in the two republics discredited the separatist option among some who might have earlier been attracted to it.

After 2014 the Ukrainian government built up the country’s armed forces, aided to some extent by Western countries, notably the USA and Canada. The president elected in the wake of the Euromaidan, Petro Poroshenko (2014-19), ran on a nationalist program, appealing much more to the West of the country than to its East and South. He reinvigorated the cult of OUN and UPA, appointing a Nationalist as head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance. He set quotas to assure that the Ukrainian language was dominant in TV and radio. This came at the expense of the Russian language, and naturally produced opposition from pro-Russian politicians. The Ukrainian language was also mandated as the exclusive language of education in state schools from the fifth grade on. This became a sore point in relations with Hungary, since there was a sizable Magyar-speaking minority in Transcarpathia.

Poroshenko also initiated a church reform that led to schism throughout the Eastern Orthodox world. Until early 2019, the Orthodox church in Ukraine was divided among three jurisdictions: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which was the largest religious organization in Ukraine and a self-governing church under the Patriarch of Moscow; the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Kyivan Patriarchate), which was not recognized by any other Orthodox church; and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church, also unrecognized and based primarily in Western Ukraine. Poroshenko, with some aid from the US state department, was able to gain the support of the Patriarch of Constantinople to establish a united Ukrainian Orthodox church that would be under the jurisdiction of Constantinople rather than Moscow. In theory, there was to be a unification council of all three Orthodox churches in Ukraine, but in reality, and unsurprisingly, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate refused to participate. In the end, a rump unification council was held between the two formerly unrecognized Ukrainian churches, and a new church came into being, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Ukraine. It was an autocephalous church under the Patriarch of Constantinople. The Patriarch of Moscow condemned the new church and its patron in Constantinople, introducing a schism in world Orthodoxy. Orthodox churches around the world had to make a choice whether to support Constantinople or Moscow. At least for the next few years (i.e., at the time this is being written), most Orthodox churches were unwilling to recognize the new Ukrainian church under Constantinople. Partially this reflected respect for the prestige and financial resources of the Russian church, and partially this resulted from resentment that Constantinople was interfering in the affairs of other churches. Parishes and communities in Ukraine were also divided. Poroshenko’s government used various administrative measures to transfer parishes from the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate to the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. This was especially successful in the politically nationalist regions of Galicia and Volhynia. At present the Ukrainian Orthodox Church [Moscow Patriarch] claims over twelve thousand parishes and the Orthodox Church of Ukraine claims over seven thousand.

Poroshenko was aiming at the consolidation of the Ukrainian nation on an ethnonationalist platform, a Ukrainian nation that spoke Ukrainian, adopted a nationalist version of history, and worshipped in a Ukrainian church. This was also, and deliberately, an attempt to de-russify Ukraine. It is difficult to say whether his efforts over five years had a positive or negative impact on healing the regional divisions in Ukraine. What is not unclear is that his policies infuriated Putin.