Three Uses of the Concept of Generic Fascism for Understanding Russia’s War Against Ukraine, by ANDREAS UMLAND

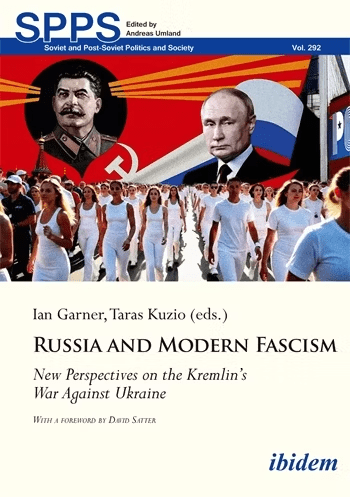

The Ukraine Solidarity Campaign has long argued that Russia’s war on Ukraine is part of a global assault on democracy and a wider resurgence of fascism and authoritarianism. Putin’s invasion is not only an attack on a sovereign nation — it is a rallying point for the far right internationally. In the UK, figures such as Nigel Farage and Tommy Robinson are Kremlin apologists, showing how the struggle in Ukraine is bound up with resisting the “new fascism” at home. In How Fascist Is Putinism? Andreas Umland examines the scholarly debate over whether Putin’s regime should be understood as fascist — and why that question matters. For those of us in the solidarity movement, the answer helps explain why Ukraine’s fight is a frontline in defending democracy everywhere. This article is based on an earlier version of a chapter from Russia and Modern Fascism: New Perspectives on the Kremlin’s War Against Ukraine, edited by Ian Garner and Taras Kuzio, foreword by David Satter (ibidem Press, September 2025, ISBN 9783838220154, 350pp, paperback, $40.00).

How Fascist Is Putinism?

Three Uses of the Concept of Generic Fascism for Understanding Russia’s War Against Ukraine

For already two decades and initially unnoted among the wider public, there has been a scholarly debate raging about whether Putinism is fascist or not.[1] The most prolific early proponents of the affirmative versus negative answers to this loaded questions have been two prominent US-based political analysts, Eastern Europe experts and public commentators – Alexander J. Motyl of Rutgers University, on the one side,[2] and Marlene Laruelle of George Washington University, on the other.[3] Motyl has, for nearly twenty years now, been publishing articles, in various languages, arguing that Putin’s regime is proto-fascist, fascistoid, or fascist (e.g., Motyl, 2007a, 2007b, 2009, 2010, 2015, 2016, 2022).[4]

In 2021, Laruelle published, after many other texts related to Russian nationalism,[5] a book titled Is Russia Fascicst? which concluded then that it is not. In 2022, the journal Nationalities Papers organized an informative discussion of Laruelle’s book (Herrera, 2022; Orenstein, 2022; Shekhovtsov, 2022; Laruelle, 2022). In 2024, her seminal volume became also available in the German language, and was complemented with a new afterword (Laruelle, 2024). In this additional text, written after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Laruelle qualified her still negative answer to whether Putinism is a form of fascism. A year later, she added an analysis of ideology in Putin’s regime where she admitted the presence of “fragmentary fascism” in it (Laruelle, 2025).

Since 2022, the prominent historian Timothy D. Snyder has become the most outspoken and frequently quoted historian of Eastern Europe to classify Russia’s regime as unequivocally fascist (e.g., Snyder, 2022).[6] After the start of Russia’s full scale invasion, the influential British-Ukrainian political scientist Taras Kuzio joined this discussion (Kuzio, 2022b).[7] In 2023, Kuzio published, in collaboration with the journalist Stefan Jajecznyk-Kelman, the first comprehensive monograph explicitly linking Russia’s full-scale invasion into Ukraine since 2022 to the concepts of fascism and genocide (Kuzio & Jajecznyk-Kelman, 2023).[8] Numerous other experts on Eastern Europe – including some Russian – have, over the last three years, also taken this or that position on the issue of whether Putin’s Russia is fascist, most of them more or less affirmatively (e.g., Epstein, 2022; Inosemzew, 2022; Straus, 2022).

What Is in a Word?

Language can attempt to describe and interpret but cannot capture the essence of the developments around us. Applying even the most established scientific notions to empirical facts is a matter of consensus rather than of truth or falsehood. The decision to use a certain word – and not another term – for labelling a phenomenon in the real world has always an element of arbitrariness. Verbal categorisations are per se neither right nor wrong. Instead, the terminology with which we conceptualise our observations is only more or less useful for their comprehension, classification and communication.

This also goes for the notion of fascism and its use after it appeared, roughly a century ago, as a generic scholarly concept in comparative analysis – rather than as a mere self-description of Benito Mussolini’s followers. Since the 1920s, “fascism” has meant many things to many observers, and suffered – as other popular generic terms like “democracy,” “socialism” or “totalitarianism” – from public overuse, political instrumentalisation and semantic inflation. For decades, there was widespread confusion and hot discussion among scholars and non-scholars about what exactly the fascist label denotes or what its intension and extension are (as documented in, among other, anthologies: Griffin, 1995, 1998; Griffin & Feldman, 2003; Griffin, Loh & Umland, 2006).

This was one of the reasons that only roughly one hundred years after the appearance of Mussolini’s Fasci d’Azione Rivoluzionaria (Bundles of Revolutionary Action) in 1914, the cross-cultural study of fascism obtained its own academic journal and scholarly society. Since the mid-1990s, there has emerged a widening consensus, among researchers from throughout the world and various disciplines, on a definition of fascism – often drawn from a seminal book on fascism’s nature by Roger D. Griffin (1991, 1993) – as a palingenetic, i.e. towards a new birth or rejuvenation, or revolutionary form of populist ultra-nationalism.[9] Against this background, a group of historians, political scientists, and representatives of other disciplines, established, in 2012, the half-yearly scholarly periodical Fascism: Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies, and, in 2015, the related International Association for Comparative Fascist Studies COMFAS (on whose board I sit).

It is telling that neither the journal Fascism nor the website of COMFAS have, so far, published anything on the question of putatively fascist traits in Putin’s ideology, regime and policies. That is because scholars know about the many complications and repercussions of assigning an abstract term to a disputed empirical phenomenon. For academics, the question is less whether Russia is fascist or not, but rather what function such a designation can fulfill[ТК1] and what cognitive risks the stretching of a concept into a new realm runs. For the case of Russia, there is moreover the problem that, in spite of a recent surge of publications on Russian political nationalism and conspiracy theories, the amount of scholarly literature on putative ultra-nationalism and fascism – especially concerning the most recent and relevant trends – is still comparatively small.[10]

The public – and not only scholarly – usage the term fascism in connection to today’s Russian state and actions has, at least, three dimensions. It is, first, a historical analogy for guiding citizens’ interpretation of current events in the light of well-known developments of the past. It is, second, a label to express a lived Ukrainian experience which is communicated for the purpose of, among others, generating international empathy. And it is, third, a generic concept for academic classification and conducting targeted comparisons across time and space.

Fascism as a Historical Analogy

Most of the public labelling of Putin’s regime as fascist, as that by Motyl (2022), Snyder (2022) or Kuzio (2023), fulfills the function of a diachronic analogy and metaphorical familiarisation for a better understanding of Putinism in Russia and Moscow’s policies in the Ukrainian occupied territories. Such historical equalisation and verbal visualisation of a current phenomenon with events in the past can serve, especially lay people, to identify key political issues and challenges in Russia today. Attributing “fascism” to Putin’s regime, in this vein, serves to illustrate and interpret, for a wider public, what is happening inside Russia and in the Ukrainian occupied territories.

Motyl (2022), Snyder (2022), Kuzio (2023), and other Eastern Europe experts argue there are numerous parallels between the domestic and foreign rhetoric and behavior of Putin’s Russia, on the one side, and Mussolini’s Italy as well as Adolf Hitler’s Germany, on the other. By early 2025, these political, social, ideological, and institutional similarities have become legion. They range from increasingly dictatorial and partly totalitarian domestic characteristics of the Russian regime to clearly revanchist and progressively genocidal features of the Kremlin’s pathological pan-nationalism towards Ukraine and Ukrainians. Snyder (2018a; 2018b; 2022) has, moreover, drawn attention to the fact that Russian official historical memory and political iconography have become – at least, covertly – pro-fascist.

In fact, already in the early phase of Putin’s rule, one could have detected such a trend in the Kremlin’s increasing embrace of the notion “Eurasian” which has entered numerous official documents since – including the “Eurasian Economic Union” founded in 2015 from the CIS Customs Union as a putative alternative to the EU (Umland, 2014, 2017). The White Russian intellectual émigré school of classical Eurasianism of the 1920s and 1930s has, as another leading historian of Eastern Europe and fascism Leonid Luks (1986, 2005, 2018) has pointed out, many similarities to the German “Conservative Revolution” of the same period (Liuks 2009a, 2009b). During the inter-war years, the proto-fascist “conservative revolutionaries” constituted a category of prominent German intellectuals – among them Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt and Ernst Jünger – who were not Nazis, yet contributed with their writings directly to the erosion of the Weimar Republic as well as indirectly to Hitler’s rise to power. The anti-liberal and anti-Western ideas of the “Conservative Revolution” (e.g., elitism, statism, collectivism, imperialism) were structurally similar to those of interwar White Russian émigré Eurasianism, as Luks (1986, 2005, 2018) and others have shown (e.g., Baissvenger, 2009). The classical Russian Eurasianism of the 1920s and 1930s is today held in high esteem by many Russian officials, propagandists, and academics (Luks, 2004; Moroz, 2010; Rossman, 2009).

The Eurasianists of the 1920s-1930s were, like their German contemporaries, radically anti-liberal, and promoted a specifically Russian “ideocratic” (i.e. ideology-ruled) order combining Asian and European traits (Schlacks & Vinkovetsky, 1996; Bassin, Glebov & Laruelle, 2015). From this perspective, the Eurasianists partly approved of the Bolsheviks’ Soviet experiment – a figure of thought also to be found in Putinism. In some regards, White Russian émigré Eurasianism was similar Stalinist National Bolshevism or Revolutionary Patriotism which has been another major reference for the shapers of today’s Putinism (Brandenberger 2002, 2010; van Ree 2003; Umland 2010; Prozorov, 2016; Zaitsev, 2023).

In recent years, Snyder and other scholars have drawn attention to another White Russian émigré intellectual of the inter- and post-war periods – Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954) who was an admirer of Italian fascism and the Nazis (Barbashin & Thoburn, 2015; Snyder, 2018a, 2018b; Pynnöniemi, 2021; Nykl, 2024). In his ruminations about a post-communist, dictatorial and nationalist Russia, Ilyin has provided, in Snyder’s words, “a metaphysical and moral justification for political totalitarianism, which he expressed in practical outlines for a fascist state. Today, his ideas have been revived and celebrated by Vladimir Putin.” (Snyder, 2018b) As Anton Barbashin (2018) added: “Ivan Ilyin is quoted and mentioned not only by the president of Russia, but by the [then] prime-minister Medvedev, foreign minister Lavrov, several of Russia’s governors, [Russian Orthodox Church] patriarch Kirill, various leaders of the [ruling] United Russia Party and many others besides.”

In late September 2022, Putin concluded his speech at the official ceremony of the (illegal) annexation of Ukraine’s Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson Oblasts citing Ilyin: “If I [Ilyin] consider Russia my Motherland, then this means that I [Ilyin] love in Russian, contemplate and think, sing and speak Russian; that I [Ilyin] believe in the spiritual strength of the Russian people. His spirit is my spirit; his fate is my fate; his suffering is my grief; its flowering is my joy.” (Putin, 2022) The link between Putinism, White Russian emigree ultra-nationalism and post-Soviet fascism became manifest, in 2023, with the foundation of the Ivan Ilyin Higher School of Politics at the Russian State University for the Humanities, and with the appointment, in 2024, of the self-professed fascist and below introduced Aleksandr Dugin (Sineokaya 2024). Dugin – even more so than Ilyin and Putin – views Western ideas and liberalism as antithetical to Russian ‘traditional values’ and Russia as a state-civilisation. Dugin has announced that he aims expunge liberal values from Russia’s education system (see the chapter in this volume by Maria Domańska).[11]

By spring 2025, the domestic and foreign policies of Putin’s Russia have accumulated many commonalities with those of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Since the start of the Russian full-scale invasion in 2022 as well as in view of its many subsequent repercussions on Russia’s external and internal affairs, the use of the fascist label to explain the character of Putin’s regime has been fulfilling educational and heuristic functions for political debates within mass media, civil society and governmental organs. If one adds several recent references by Putin and his entourage to historical Russian proto- or pro-fascism, such as the inter-war Eurasianists and White Russian emigrees like Ilyin, it appears today as more legitimate than before 2022 to characterize Putinism as Russian fascism.[12]

To be sure, many comparative historians and political scientists would, as shown below, still insist that Putinism is not strictly fascist. These arguments notwithstanding, the regimes of Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany as well as their policies are chronologically and substantively sufficiently close to those of Putin’s Russia to justify their comprehensive comparison and partial equation. Italian Fascism and German Nazism are today the most widely known historical examples with which one can illustrate – for a wider public – the nature and direction of Putin’s regime and imperial nationalism towards Russia’s neighbours and the outside world.

Fascism as a Lived Experience

The application of “fascism” to Putin’s regime aims to impress upon audiences outside Ukraine a clearer understanding of political affairs in Putin’s Russia as well as its international behavior. In contrast, the Ukrainian use of the term fascism and neologism “Ruscism” – a combination of “Russia” and “fascism” pronounced “rashyzm” – is, above all, an expressive act. Within Ukraine, the fascist labelling of Russia articulates the collective shock, grief and desperation in the face of the morbid cynicism, demonstrative ruthlessness, and thinly veiled sadism of the Kremlin’s policies vis-à-vis ordinary Ukrainians – especially, since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The use of fascism fulfils, for the Ukrainian government and civil society as well as for their foreign supporters, also the function of a battle cry to mobilise domestic and international support for resistance against Russian military aggression.

Already before the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022, many outrageous statements by Russian governmental representatives, parliamentarians, and state-media workers illustrated, the intentions of Russia regarding Ukraine (Davis, 2024). This discourse indicated that Moscow’s aims go far beyond a mere redrawing of state borders, reassertion of regional hegemony, and refuting a Westernisation of central-eastern Europe. Since 2014, the Kremlin has been engaged on Crimea and the Donbas in a systematic campaign of eradication of Ukrainian identity, culture and patriotism as well as in forced Russification of these occupied territories (see Hurska, 2019, 2023, 2024a, 2024b; McGlynn, 2023; Oliinyk, 2023; Hird, 2024). Since 2022, adjectives such as “fascist” and “Ruscist” are meant to signify that Russia’s military aggression is not only about the conquest of Ukrainian territory but also about the destruction of Ukraine as an independent nation-state and cultural community separate from Russia (Finkel, 2023; Davis, 2024). The words and deeds of Putin’s Regime – i.e. of the President, Russian government, Russian military, and Kreml-controlled media – are today largely congruent in this regard.

It would go too far, to be sure, to equalize Putin’s Russia’s Ukrainophobia with the Nazis’ biological racism and eliminationist antisemitism. It is only in some respect in which Russian behavior closely resembles German one, such as in the deportation and denationalisation of Ukrainian children (Umland, 2024) that reminds of policies towards, among others, Polish children. With its irredentist war, Moscow aims to eradicate the Ukrainian nation as a self-conscious polity and society, and return them to their ‘Little Russian’ roots, rather than to physically eliminate all Ukrainians, as the Third Reich attempted to do with the Jews. Nevertheless, the Russian agenda in Ukraine does not only mean displacement, harassment, deportation, re-education and brainwashing of Ukrainians to russify them. It also includes mass expropriation, terrorisation, incarceration, torture and murder of those Ukrainians who resist, by word or/and deed, Russia’s attempted military expansion, political rule and cultural dominance over Ukraine.

The Kremlin’s genocidal agenda in Ukraine is presented as a plan to “denazify” Ukraine. The term “denazification” has historic meaning as a name of the anti-Hitler coalition’s policies in occupied Germany during the second half of the 1940s and beyond. The Kremlin’s use of “denazification” in relation to its aims in occupied Ukraine is not only different from that of the post-war Allies. It represents a revival, in Putin’s Russia, of the extensive Soviet propaganda campaigns against Ukrainian ‘bourgeois nationalists’, fascists and Nazi collaborators as well as an attempt to claim the so-called ‘Special Military Operation’ as a second run of the Great Patriotic War.

Within the peculiar context of the Soviet and post-Soviet Russian discourse on fascism, a labelling of Russia’s russification policy in Ukraine as “denazification” makes certain sense. In both, the Soviet Union and Russian Federation, terms like “Nazi” and “fascist” have been used, by governmental officials and propagandists, not only and not so much to classify Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany (an official Soviet ally in 1939-40). Instead, “fascism” has been misused in the USSR to attack any Ukrainian who defended the Ukrainian language and culture, protested against Russification, and sought greater autonomy for the Ukrainian SSR or Ukraine’s independence. Similarly, in Putin’s Russia “fascist” is used against any Ukrainian who holds an identity distinct from Russian and seeks a Ukrainian future outside the “Russian World.” More recently, Kremlin disinformation campaigns have used the Nazi term more broadly against the EU, the UK, and others accused of ‘Russophobia’.[13]

In the context of the Russo-Ukrainian War, Snyder and Epstein (2022) have aptly classified the Russian use of “fascism”, “Nazism” and “denazification” as “schizofascist.”[14] Russian state officials and propagandists whose worldviews have similarities to that of inter-war fascists use – schizophrenically – the terms “Nazism” and “fascism” to denigrate Ukrainians who possess an identity distinct from Russians, and do not uphold a ‘Little Russian’ or pan-Russian identity. The Kremlin and its media channels do so to explain to their various domestic and foreign audiences the ferocity of Russia’s violent anti-Ukrainian campaign. A labelling of Ukraine as “fascist” is meant to rationalise the Kremlin’s large-scale terror against Ukrainian civilians, deportation of thousands of unaccompanied children (Umland, 2024), mass torture of prisoners of war, and targeted attacks on cultural institutions such as libraries, churches, schools and theatres. The Ukrainian prosecutor’s office has collected over 150,000 war crimes committed by Russian forces in Ukraine in the first three years of the large-scale war.[15] Supposedly, Moscow’s harsh measures are part of a mere Russian defense against the ‘Kyiv regime’ of Nazi Ukraine which is a Western puppet state (Kragh & Umland, 2024). This dualistic narrative also aggravates the cruelty and lethality of the Russian troops’ behavior on the spot, in Ukraine.

Russia’s verbal and practical viciousness vis-à-vis Ukraine is also the reason for the wide use of “fascism” by Ukrainians commenting Russian policies in the occupied territories. There is little wonder that most Ukrainian civilians – not to mention those on the frontline – are labelling Russian genocidal behavior as “fascist.” Millions of Ukrainians, who have stayed in Ukraine in 2022 or returned home after fleeing abroad, directly experience the Kremlin’s war, on a weekly basis. Many Russian missile, glide-bomb and drone attacks into the Ukrainian rear do not target military objects or armament factories. Instead, they are flown, with obvious purpose, into civilian buildings or places that have no direct relation to Ukraine’s defense efforts, and include apartment houses, supermarkets, hospitals, and educational institutions. In only one week in March 2025, Russia launched 1,200 bombs, 870 drones and over 80 missiles against Ukraine.[16]

Professional historians of war may argue that intentional attacks on civilian populations and infrastructure are not unique to fascist warfare. Nevertheless, the label of fascism comes first to mind to most Ukrainians when conceptualizing such attacks. Some older Ukrainians still remember the German war against the USSR. A Jewish-Ukrainian Holocaust survivor from Odesa, Roman Shvartsman, told the German parliament Bundestag in January 2025, at the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp: “Hitler wanted to kill me as a Jew. Putin is trying to kill me because I’m Ukrainian.”[17]

Political comparativists may still argue that the ideology of Nazism is different from Putinism. The political ideas that stand behind Russia’s war against Ukraine since 2014 are indeed – unlike the Third Reich’s ones – not rooted in biological racism or eliminationist antisemitism. However, the material repercussions of these dissimilar agendas are sufficiently comparable to most Ukrainians to warrant for them the labelling of their experience with Moscow’s warfare against Ukraine as “Russian fascism.”

Fascism as a Scholarly Concept

An increasing number of prominent area experts on central-eastern Europe, like Motyl (2022), Snyder (2022) or Kuzio (2023), define Putin’s twenty-first century Russia as fascist. In contrast, most comparative historians and political scientists who study twentieth century fascism from a cross-cultural perspective are either avoiding or questioning the usage of “fascism” to categorize Putinism. This has much to do with the usually narrower definitions of generic fascism that many academics continue to use. The, perhaps, most widely recognised of these scholarly notions is that of Roger D. Griffin, an influential British historian of ideas who, in the 1990s, conceptualised generic fascism as a “palingenetic form of populist ultra-nationalism.” (Griffin, 1991, 1993) The core trait that, according to Griffin and other comparativists, distinguishes fascists from other right-wing activists is their aim of a political, social, cultural and anthropological revolution. A thorough palingenesis or rebirth of the contemporary degenerated nation needs to be fundamentally rejuvenated, cleansed and transformed into a newborn collective. This palingenesis should also create a new fascist man (and sometimes woman) ready to suffer, fight, kill and die for his (or her) national community – whether defined in ethnic, racial, linguistic, religious, civilizational or/and other terms.

Fascists often refer to an alleged Golden Age in their nation’s distant history and use ideas as well as symbols from past periods. Yet, they do not want to preserve or return to a bygone era, but rather create an entirely novel national community, state or/and empire. Fascists are on the extreme right, yet they are revolutionaries rather than ultra-conservatives.

Griffin’s concept and similarly narrow notions by other scholars set clear limits to the denotation of fascism and number of fascist regimes as well as movements in human history. Their definitions imply that there have only been two independent fascist states – Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany. In addition, there were fascist governments installed by the Nazis such as those of the Hungarian Arrow Cross and Croatian Ustasa. Finally, there have been many clearly fascist parties, as well as hundreds of other intellectual, semi-political and terror groups as well as so-called “groupuscules” across the world, since the late 19th century, that can be classified as proto- or fully fascist (Griffin, 1995, 1998, 2003, 2019, 2020).

Restrictive conceptualisations of generic fascism, such as that by Griffin, purposefully exclude such putatively fascist regimes as those of Kemal Atatürk in Turkey[ТК2] [AU3] , Franco[ТК4] [AU5] in Spain, Salazar in Portugal[ТК6] [AU7] or Peron in Argentina. While also populist, nationalist and non-democratic, like the rules of Mussolini or Hitler, Kemalism, Francoism, Salazarism and Peronism were not sufficiently palingenetic and/or integral to warrant their labelling as fascist. A similar argument would today be made, by many comparativists of international fascism, about Putinism. Putin’s Russia seeks a restoration of the Russian empire but perhaps not the creation of a rejuvenated Russian state, nation and man.[18]

On the other hand, during the last 25 years, Putinism has evolved in terms of its goals and rhetoric as well as its implemented policies and actions. Putin launched his political career in the1990s with Russia’s two most prominent pro-Western democrats, the first mayor of post-Soviet St. Peterburg Anatoliy Sobchak and first President of the Russian Federation Boris Yeltsin. After Putin had become prime minister in 1999 and president in 2000, Putinism contained, for several years, liberal and pro-European traits. Russia continued, under Putin in the 2000s and early 2010s, to be a regular member of the Council of Europe, NATO-Russia Council, as well as G8 Group. Russia even negotiated a deep partnership agreement with the European Union until the start of the first invasion of Ukraine in 2014.

At the same time, Putin’s Russia has, for the last 20 years, moved ideologically more and more to the nationalist right as well as structurally towards para-totalitarianism, initially in reaction to the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine. Among others, Moscow launched the Russian World Foundation and TV propaganda channel “Russia Today” (later RT), re-unified the domestic and emigre Russian Orthodox Churches, or re-buried Ivan Ilyin from Zurich to Moscow. To be sure, Russia’s domestic regression from proto-democracy to dictatorship had already begun with Putin’s entry into high politics in 1999. Yet, it was only eight years later when Putin, with his 2007 Munich Security Conference speech, announced Russia’s turn away from the West. Since then, Putinism has been becoming more illiberal, anti-Western, imperialist, nationalist, and bellicose, by the year. The only fluctuation in this evolution occurred during Dmitrii Medvedev’s “palliative presidency” of 2008-2012. Even so, it was during Medvedev’s presidency when Russia invaded Georgia in 2008 and de facto annexed the Tskhinvali Region (“South Ossetia”) and Abkhazia. A year later, Medvedev sent a threatening, undiplomatic list of demands to Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko.

Subsequently, the Russian para-democratic pseudo-federation transformed from a hybrid into a fully-fledged authoritarian and increasingly imperialistic regime – as documented by, among others, Åslund (2008), Bacon (2015), Barkanov (2020), Bassin & Suslov (2016), Blakkisrud & Kolstø (2016, 2018), Casula & Tipaldou (2019), Eltchaninoff (2016), Gorenburg, Pain & Umland (2012a, 2012b), Horvath (2012), Kragh & Umland (2024), Mitrofanova (2005), Shekhovtsov (2017a), Umland (2009, 2018), van Herpen (2013), and Zygar (2016). After the 2020 change of Russia’s Constitution made Putin de facto life president and mass repression swept the country, Russia became a dictatorship. Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and parallel turn to the East were, at that point in time, extrapolations rather than reversals of a transformation that had been taking place since the mid-2000s, if not before.

For most comparativist scholars, these and similar changes, during the last quarter of a century, would continue to be insufficient to classify Putinism as fascism. Nevertheless, the transmutation of Russian domestic and foreign affairs has had a clear direction and is becoming ever deeper. It has meant – and continues to mean – a constant increase of rhetorical aggression, internal repression, external escalation, and general radicalisation culminating in Russian thinly-guised nuclear threats towards the ‘collective West’ and ‘Kyiv regime’ (Ukraine).

One of the signs of this tendency is the recent rise to prominence of the notorious war propagandist and amateur philosopher Dugin who, in the 1990s, repeatedly admitted his allegiance to fascism (e.g., Dugin, 1992). Among others, Dugin declared in his 1997 article “Fascism – borderless and red” that, after inconsistent implementation of the fascist idea during inter-war and World War II periods in Italy and Germany, post-Soviet Russia would finally create a “genuine, true, radically revolutionary and consistent, fascist fascism.”[19] Over the following quarter of a century, Dugin’s star went up and down in the Russian mass media, intellectual debates, and political discourse.[20] His influence over the Russian government was often overstated to allegedly be, as some commentators put it, “Putin’s brain” (e.g., Barbashin & Thoburn, 2014). This was, at least until 2014, an overstatement of the self-ascribed “neo-Eurasianist” influence on Putin’s Russia and its policies (Shekhovtsov, 2014; Kalinin, 2019). Since 2022, however, Dugin’s presence in Russian public life has indeed increased. While he is still not the chief ideologist of Putinism, Dugin has recently become a semi-official apologist and theoretician of the Russian leadership’s deepening anti-Western turn.

This development is linked to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine as an escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War which Dugin had been promoting in, among others, his magnum opus The Foundations of Geopolitics, since the 1990s (Dugin, 1997, 2000). Dugin’s rise to central policymaking is likely also a result of, among others, a spectacular 2022 assassination attempt on him which failed, but killed his 30-year old daughter Daria Dugina. Shortly afterward, President Putin referred, in his speech at Russia’s illegal annexation of Ukraine’s four Oblasts, to enemies of Russia who “encroach on our philosophers” (Putin, 2022) – an obvious reference to the assassination attempt on the Dugin family. In spring 2024, Dugin was interviewed by Tucker Carlson, and their conversation had been clicked by over a million Youtube viewers of the English original version by the end of 2024.[21] Since then, Dugin has become frequent interviewee and reference in US ultra-conservative mass and social media.

The new prominence of Dugin in and outside Russia, and his above-mentioned appointment at an institute named after Ilyin, who has been frequently quoted by Putin, is indicative of larger trends within Russian political and civil society. While it would have been misleading to speak of fascist trends within Putin’s regime 20 years ago, the rise of Dugin and some other new features of Russian official ideology, rhetoric, propaganda and policy have brought Putinism closer to fascism. It may be still misleading to classify Putin as a domestic revolutionary ultra-nationalist[ТК8] . Yet, his regime is increasingly incorporating right-wing extremist ideas and now unashamedly includes coded fascist references into its official vocabulary.

Moreover, Russia’s policies in the occupied Ukrainian lands could be categorised as quasi-fascist in a more direct sense. Already before the war, the issue of Ukraine’s fate played a major role in Russian imperialist nationalism, as analyzed from different viewpoints by, among others, Finkel (2024), Gretskiy (2020), Kuzio (2022a), Pakhlevska (2011a, 2011b), and Plokhy (2018). As Mitrokhin (2015, 2019), Shekhovtsov (2017b), Hauter (2023) and others have shown, Russian ultra-nationalist – including fascist – ideologues and activists were closely involved in the start of Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2014.

Since then, the Russian state has been conducting a ruthless de-Ukrainization and Russification campaign in those parts of Ukraine it controls via mass terror, forced re-education and material incentives (see Hurska, 2019, 2023, 2024a, 2024b; McGlynn, 2023; Oliinyk, 2023; Finkel, 2024; The Kremlin’s Occupation Playbook, 2024). Millions of Ukrainian civilians – including and especially children and teenagers – from the occupied parts of Ukraine are targeted by Moscow’s administrators, cultural workers, pseudo-journalists, professors, and teachers for de-Ukrainianisation and Russification – often, after their displacement or deportation. To be sure, such irredentist, colonising and homogenising policies are not necessarily labelled as fascist, in the comparative study of imperialism. Yet, the instruments Russia deploys in implementing these policies and their envisaged results are often similar to those of fascist revolutions in Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany.

The Kremlin seeks to fundamentally remake occupied Ukraine and to ‘return’ Ukrainians to their allegedly Russian roots, claiming that an independent Ukrainian national identity is an artificial construct imported by Western conspirators seeking to divide the larger ‘Russian people’. Pan-Russian nationalists see Ukraine – mostly, with exception of Eastern Galicia (i.e. the Lviv, Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts) – as originally Russian lands and call them “New” and “Little Russia” (Novorossiia, Malaia Rossiia).[22] Ukrainians are, according to Russian pan-nationalists, merely one of three branches of a triune (or trinity of) pan-Russian people or ‘Holy Rus’ composed of Great, Little, and White Russians, i.e. Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians respectively. The Ukrainian language, for such Russian pan-nationalists, is a dialect of the Russian language. Ukrainian literature, music, painting, philosophy, and religion, constitute, according to the ideology of pan-Russianism, merely a regional folklore rather than a distinct national culture.

The people living “na Ukraine” – i. e., “on [a landscape called] Ukraine” – are understood, by Russian pan-nationalists as inhabitants on the edge (okraina) of Greater Russia. From their point of view, Ukraine is a Russian border region rather than an independent country. The West Russian “borderlanders” have been, in this narration of East European history, misled by anti-Russian forces in the West – e.g., Austrians and Poles in the late nineteenth century, Western security services, the US, or the EU since 1991 – to believe they are a self-sufficient nation. Western conspirators and USSR leader Vladimir Lenin, who foolishly gave Ukrainians a Soviet republic, have divided the larger ‘Russian’ people and thereby estranged the “Little Russians” (malorossy) from the “Great Russians” (velikorossy).

Russian occupational policies to reverse this allegedly foreign-induced intra-civilisational alienation could be conceptualised as an attempt to conduct a rebirth or palingenesis of Greater Russia as a triune pan-Russian people, a step to reconstituting what had been the eastern Slavic core of the Soviet Union (see the chapter by Garner and Kuzio). The Kremlin’s aim in occupied Ukraine can been defined as an attempt to fashion a political, social, cultural and anthropological revolution. Campaigns to homogenise populations, to be sure, have been frequent in the history of nation-states and empires, and are not therefore exclusive to fascism. At the same time, the Russian annexation of Ukraine’s southeast and Crimea, and their de-Ukrainianisation and Russification are sufficiently similar to classical fascist domestic and occupation policies to see them as quasi-fascist.

Conclusion

“Fascism” is, in the English language, a succession of seven letters. When and where to use the word is in the eye of the beholder. In academic analysis, the key question is how a term is defined and conceptualised by the scholar. Which peculiar semantic intension does a classificatory taxon contain, and which exact empirical extension emerges from this or that notion of the term?

Russia – or any other object – “is” neither fascist, nor non-fascist, nor semi-fascist. Instead, the question is what different users of “fascism” understand when they apply the term this or that case. Some historical and political analysts, like Motyl, Snyder and Kuzio, seek to establish a historical analogy between Putinism and inter-war Italian Fascism as well as German Nazism. In this volume, Garner and Kuzio seek to, as they see it, modernise fascism as a term that can be applied to twenty first century Russia. Many Ukrainians refer to fascism as the closest example from their lands’ recent historical experience to what their country is going through today. Most comparativists aim to classify Putinism within a wider semantic field containing not only “fascism,” but also such concepts as “authoritarianism,” “conservatism,” “reaction,” “irredentism,” “restoration,” etc.

In view of the historic events since 2022, the gap in the use of “fascism” for Putin’s Russia mentioned at the outset, between, on the one side, Motyl & Co., and, on the one side, and Laruelle & Co., on the other, has become closer. In her latest extensive outline on ideology under Putin of 2025, Laruelle admits:

“With the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the nature of the regime has changed; one can now identify a fragmentary fascism. On the one hand, the so-called party of war – the siloviki apparatus, the military bloggers, the paramilitary and militia realms – calls for a total war with Ukraine (conquering Kyiv and not just the currently occupied territories), for an open war with the West, and for a full mobilization of Russian society that would put culture and economy alike entirely on a war footing. These groups do share a fascist imaginary: they believe in regeneration through violence, with all the aesthetics that fascism implies. But in opposition to them, one can still identify a large part of the political establishment (the technocratic part) that wants the special operation to remain just that, “special” – that is, without any implications for the country as a whole.” (Laruelle, 2025: 142)

As a result of this ambivalence in the leadership, even after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and its various after-effects on domestic matters, Russian internal social, political and cultural affairs remain far from ideal-typical fascism. With regard to Russia herself, Putin and most of his entourage are not futuristically driven revolutionaries, but rather nostalgia-inspired representatives of the pre-1991 ancien regime. They seek an as far-reaching as possible restoration of the old Tsarist and Soviet orders rather than the birth of an entirely novel empire and world – as Dugin, among other Russian fascists, envisages. In this sense, Putin is not Russia’s Hitler but rather a partial equivalent to Germany’s last Reichspräsident (Imperial President) Paul von Hindenburg who represented pre-1918 Imperial Germany and made Hitler Reichskanzler (Imperial Chancellor) on 30 January 1933 (Kailitz & Umland, 2016, 2019). Even with regard to Russia’s genocidal policies in the territories it has occupied in Ukraine, one could point out that the Nazis did not invent genocide; among others, Belgium in the Congo in the late nineteenth century and imperial Germany in Namibia in the early twentieth century committed genocide against colonised native peoples.

On the other hand, within the larger ideological camp of Russian imperial nationalism, Ukraine is not a foreign country or strange colony but rather one of three branches of a triune pan-Russian people. Most outside observers regard the Kremlin’s military, occupational and cultural policies towards Ukraine as a matter of Russian international affairs. Yet, many Russians would regard them as their own country’s internal matter. Russian viciousness, radicalness and lawlessness towards Ukrainians has much to do with most Russians’ assumption that this is a family affair where legal rules, human rights, and international regulations do not apply. In the absence – except for a brief period in the 1990s – of adequate historical memory policies, post-Soviet Russia has not yet to come to terms with the – often, horrendous – mass crimes committed by the Tsarist and Soviet states, in the name of the Orthodox or Communist Russian people, mission and empire.

To many victims and close observers of what Russia is undertaking in Ukraine, most comparativists’ relative silence on, or open rejection of, using the fascist label for Putin’s Russia appears as inappropriate, disingenuous and even immoral. Russia’s armed forces and occupational administration in Ukraine behave, especially since 2022, in a manifestly terroristic, genocidal, ecocidal, and sometimes even sadist manner. Against this dreadful background, it seems strange to insist that Russia’s policies and the ideas behind them are clearly, absolutely and unquestionably non-fascist.

To be sure, there are and hopefully will be no Russian equivalents to the Nazis’ gas chambers and extermination camps (as there were also none such Italian equivalents). Yet, how does one categorise informatively Russia’s genocidal intentions behind the mass murders in Bucha or Mariupol in 2022, the explosion of the Kakhovka Dam in 2023, the mass deportation of unaccompanied children, and the many other Russian exceptional digressions against Ukrainian civilians (Umland, 2024)? Why are almost ninety percent of Ukrainian POWs in Russian custody, as the UN reported in 2024, being tortured?[23] These crimes constitute neither cases of collateral damage from military operations nor permutations of ordinary colonial policies to be found under all occupational regimes. A cautious labelling of the mentality or ideology behind Russia’s annihilation war in Ukraine as “illiberal,” “conservative,” “traditionalist” or “backward-looking” seems insufficient and even misleading by most students familiar with Russia’s so-called “denazification” policies in occupied Ukraine.

On the other hand, an unequivocal classification of Putinism as a Russian form of fascism may also be unhelpful (Laruelle, 2021, 2024). An exclusive explanation of Russia’s motivation for its policies in Ukraine and elsewhere with ultra-nationalist maximalism limits understanding of the motivations behind the so-called ‘Special Military Operation’ in Ukraine. To be sure, there are numerous fascists in today Russia, including in its political and intellectual elites. Yet, many of Russia’s key policymakers are immoral cynics rather than ideological fanatics (Zygar, 2016; Laruelle, 2025).

A major – if not the crucial – driver behind Putin Russia’s foreign adventures before 2022 was their political easiness, strategic predictability, military victoriousness, economic inconsequentiality and domestic popularity (Greene & Robertson, 2022). Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, as well as the military intervention in Syria in 2015 were successful because there was relatively little push back from those affected – and from the international community. As shown by, among others, Vicente Ferraro (2023), these military adventures not only politically and financially cheap undertakings for the Kremling, but even had a stabilising effect on Putin’s regime (see also: Snegovaya, 2019, 2020).

Against the background of such positive repercussions, the Kremlin decided to launch a full-scale invasion believing there would be again no significant push back from Ukrainians and that many “Little Russians” would even greet the Russian army as liberators, while the West would again, as in 2008 and 2014, do little. To be sure, the Kremlin was wrong on all three counts. It made a miscalculation in so far as Russia’s escalated war against Ukraine has, since 2022, led to a more fundamental and presumably unintended conflict about the future of Europe. The initial impulse for the full-scale invasion was, nevertheless, less growing ultra-nationalist fanaticism than misinformed power-political cynicism within Putin’s regime.

Despite the prevalence of non-fascist factors determining the start of the full-scale invasion, already existing fascist tendencies in Russia’s society and polity have been strengthening by the year since 2022. Aleksandr Dugin’s rising public presence, in both Russian and international media, during the last three years is one of many indicators illustrating that, in Laruelle’s (2025) words, “fragmentary fascism” is increasing within Putin’s regime. The longer and the more successful Russia’s war against Ukraine is, the more prominent and influential fascist Russian actors, ideas and networks will become in Russia as well as beyond.

References

Arnold, Richard. 2016. Russian Nationalism and Ethnic Violence: Symbolic Violence, Lynching, Pogrom and Massacre. Abindgon, UK: Routledge.

Arnold, Richard, and Ekaterina Romanova. 2013. “The White World’s Future? An Analysis of the Russian Far Right.” Journal for the Study of Radicalism 7(1): 79-108.

Arnold, Richard, and Andreas Umland. 2018. ‘The Radical Right in Post-Soviet Russia’, in Jens Rydgren (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 582-607.

Åslund, Anders. 2008. “Putin’s Lurch toward Tsarism and Neoimperialism: Why the United States Should Care.” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 16(1): 17–25.

Bacon, Edwin. 2015. “Putin’s Crimea Speech, 18 March 2014: Russia’s Changing Public Political Narrative,” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 1(1): 13-36.

Baissvenger [Beisswenger], Martin. 2009. “‘Konservativnaia revoliutsiia’ v Germanii i dvizhenie evraziitsev: tochki soprikosnoveniia.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(2): 23-40.

Barbashin, Anton. 2018. “Ivan Ilyin: A Fashionable Fascist.” Riddle, 20 April. https://ridl.io/ivan-ilyin-a-fashionable-fascist/

Barbashin, Anton, and Hannah Thoburn. 2015. Putin’s Brain: Alexander Dugin and the Philosophy Behind Putin’s Invasion of Crimea. Foreign Affairs, 31 March 2014 https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-03-31/putins-brain (accessed April 7th, 2025).

Barbashin, Anton, and Hannah Thoburn. 2015. Putin’s Philosopher: Ivan Ilyin and the Ideology of Moscow’s Rule. Foreign Affairs, 20 September. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2015-09-20/putins-philosopher (accessed December 7th, 2016).

Barkanov, Boris. 2020. “A Realist View from Moscow: Identity and Threat Perception in the Writings of Sergei A. Karaganov (2003–2019),” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 6 (2): 57-112.

Bassin, Mark. 2008. Eurasianism ‘Classical’ and ‘Neo’: The Lines of Continuity, in: Tetsuo Mochizuki, ed. Beyond the Empire: Images of Russia in the Eurasian Cultural Context. Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, 279–294.

Bassin, Mark. 2016. The Gumilev Mystique: Biopolitics, Eurasianism, and the Construction of Community in Modern Russia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bassin, Mark, Sergei Glebov, and Marlene Laruelle, eds. 2015. Between Europe and Asia: The Origins, Theories and Legacies of Russian Eurasianism. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Bassin, Mark, and Mikhail Suslov, eds. 2016. Eurasia 2.0: Russian Geopolitics in the Age of New Media. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Berglund, Krista. 2002. The Vexing Case of Igor Shafarevich, a Russian Political Thinker. Basel: Springer.

Blakkisrud, Helge, and Pål Kolstø, eds. 2016. The New Russian Nationalism: Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism 2000-15. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Blakkisrud, Helge, and Pål Kolstø, eds. 2018. Russia Before and After Crimea: Nationalism and Identity, 2010–17. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2018.

Borenstein, Eliot. 2019. Plots Against Russia: Conspiracy and Fantasy After Socialism. Ithaka, NY: Cornell University Press.

Brandenberger, David. 2002. National Bolshevism: Stalinist Mass Culture and the Formation of Modern Russian National Identity, 1931-1956. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brandenberger, David. “Stalin’s Populism and the Accidental Creation of Russian National Identity.” Nationalities Papers 38.5 (2010): 723–739.

Brown, Stephen, and Konstantin Sheiko. 2014. History as Therapy: Alternative History and Nationalist Imaginings in Russia. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Casula, Philipp and Tipaldou, Sofia. 2019. “Russian Nationalism Shifting: The Role of Populism Since the Annexation of Crimea.” Demokratizatsiya 27(3): 349-370.

Clover, Charles. 2016. Black Wind, White Snow: The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Coalson, Robert. 2022. “Nasty, Repressive, Aggressive — Yes. But Is Russia Fascist? Experts Say ‘No.’” Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 9 April. https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-repressive-aggressive-not-fascist/31794918.html

Cucută, Radu Alexandru. 2015. “Flogging the Geopolitical Horse.” Europolity: Continuity and Change in European Governance 9(1): 227-233.

Danlop [Dunlop], Dzhon [John] B. 2010. “‘Neoevraziiskii’ uchebnik Aleksandra Dugina i protivorechivyi otklik Dmitriia Trenina.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 7(1): 79-113.

Davis, J. (2024). In Their Own Words: How Russian Propagandists Reveal Putin’s Intentions. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Dugin, Aleksandr. 1992. Konspirologiya: nauka o zagovorakh, taynykh obshchestvakh i okkul’tnoy voyne. Moskva: Arktogeia.

Dugin, Aleksandr. 1997. Osnovy geopolitiki: geopoliticheskoe budushchee Rossii. Moskva: Arktogeia.

Dugin, Aleksandr. 2000. Osnovy geopolitiki: geopoliticheskoe budushchee Rossii. Myslit’ prostranstvom. 4th expanded edn. Moskva: Arktogeia-Tsentr.

Duncan, Peter J.S. 2000. Russian Messianism: Third Rome, Revolution, Communism and After. London: Routledge.

Eltchaninoff, Michel. 2016. In Putins Kopf: Die Philosophie eines lupenreinen Demokraten. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta Verlag.

Epstein, Mikhail. 2022. “Schizophrenic Fascism: On Russia’s War in Ukraine,” Studies in East European Thought 74, no. 4: 475–481.

Feldman, Matthew. Ed. (2008). A Fascist Century: Essays by Roger Griffin. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ferguson, Niall, and Brigitte Granville. 2000. “‘Weimar on the Volga:’ Causes and Consequences of Inflation in 1990s Russia Compared with 1920s Germany.” Journal of Economic History 60 (4): 1061-1087.

Ferraro, Vicente. 2023. ‘Why Russia invaded Ukraine and how wars benefit autocrats: The domestic sources of the Russo-Ukrainian War.’ International Political Science Review 45(2), 170-191.

Finkel, Eugene. 2024. Intent to Destroy: Russia’s Two-Hundred-Year Quest to Dominate Ukraine. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Fish, Steven M. 2017. “What is Putinism?” Journal of Democracy 28 (4): 61-75.

Gorenburg, Dmitry, Emil Pain, and Andreas Umland, eds. 2012a. The Idea of Russia’s “Special Path” (Part I): Studies in Russian Intellectual History, Political Ideology, and Public Opinion. Special issue of Russian Politics and Law 50(5). Transl. S. Shenfield. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Gorenburg, Dmitry, Emil Pain, and Andreas Umland, eds. 2012b. The Idea of Russia’s “Special Path” (Part II): Studies in Post-Soviet Russian Political Ideas, Strategies and Institutions. Special issue of Russian Politics and Law 50(6). Transl. S. Shenfield. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Greene, Samuel A. and Graeme B. Robertson. 2022. Putin vs. the People: The Perilous Politics of a Divided Russia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gretskyi, Igor. 2020. “Lukaynov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy – The Case of Ukraine.” Saint Louis University Law Journal 64(1): Art. 3, 1-21.

Griffin, Roger. 1991. The Nature of Fascism. London: Pinter.

Griffin, Roger. 1993. The Nature of Fascism. 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

Griffin, Roger. Ed. 1995. Fascism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Griffin, Roger. Ed. 1998. International Fascism: Theories, Causes and the New Consensus. London: Arnold.

Griffin, R. (2003). From slime mould to rhizome: an introduction to the groupuscular right. Patterns of Prejudice, 37(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322022000054321

Griffin, Roger. 2007. Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Giffin, R. 2014. “Palingenetischer Ultranationalismus: Die Geburtswehen einer neuen Faschismusdeutung”. Der Faschismus in Europa: Wege der Forschung, edited by Thomas Schlemmer and Hans Woller, München: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2014, pp. 17-34.

Griffin, Roger. 2018. Fascism: An Introduction to Comparative Fascist Studies. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Griffin, Roger. 2020. Faschismus: Eine Einführung in die vergleichende Faschismusforschung. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Griffin, Roger with Matthew Feldman. Eds. (2003) Fascism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. 5 vols. London: Routledge.

Griffin, Roger, Werner Loh, and Andreas Umland, eds. 2006. Fascism Past and Present, West and East: An International Debate on Concepts and Cases in the Comparative Study of the Extreme Right. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Griffiths, Edmund. 2022. Aleksandr Prokhanov and Post-Soviet Esotericism. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Gudkov, Lev. 2011. “The Nature of ‘Putinism.’” Russian Social Science Review 52, no. 6: 21–47.

Hanson, Stephen E. 2006. “Postimperial Democracies: Ideology and Party Formation in Third Republic France, Weimar Germany, and Post-Soviet Russia.” East European Politics and Society 20 (2): 343-72.

Hanson, Stephen E. 2010. Post-Imperial Democracies: Ideology and Party Formation in Third Republic France, Weimar Germany, and Post-Soviet Russia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hanson, Stephen E., and Jeffrey Kopstein. 1997. “The Weimar/Russia Comparison.” Post-Soviet Affairs 13 (3): 252-83.

Hauter, Jakob. 2023. Russia’s Overlooked Invasion: The Causes of the 2014 Outbreak of War in Ukraine’s Donbas. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Herrera, Y. M. (2022). Who’s a Fascist? Nationalities Papers, 50(6), 1248–1251. doi:10.1017/nps.2021.103

Hird, Karolina. 2024. “The Kremlin’s Occupation Playbook: Coerced Russification and Ethnic Cleansing in Occupied Ukraine,” Institute of War, 9 February. https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlins-occupation-playbook-coerced-russification-and-ethnic-cleansing-occupied.

Höllwerth, Alexander. 2007. Das sakrale eurasische Imperium des Aleksandr Dugin: Eine Diskursanalyse zum postsowjetischen russischen Rechtsextremismus. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Horvath, Robert. 2012. Putin’s Preventive Counter-Revolution: Post-Soviet Authoritarianism and the Spectre of Velvet Revolution. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Hurska, A. (2019). ‘Ukraine’s Occupied Donbas Adopts Russia’s Youth Militarization Policies,’ Eurasia Daily Monitor, 16 (77), 28 May. https://jamestown.org/program/ukraines-occupied-donbas-adopts-russias-youth-militarization-policies/

Hurska, A. (2023). ‘Generation Z: Russia’s Militarization of Children,’ Eurasia Daily Monitor, 20 (134), 18 August. https://jamestown.org/program/generation-z-russias-militarization-of-children/

Hurska, A. (2024a). ‘Russia is Breeding for War Through Youth (Para-)Militarization,’ Eurasia Daily Monitor, 21 (22), 13 February. https://jamestown.org/program/russia-is-breeding-for-war-through-youth-para-militarization/

Hurska, A. (2024b). ‘Russia Converts Ukrainian Children Into Enemies,’ Eurasia Daily Monitor, 21 (36), 7 March. https://jamestown.org/program/russia-converts-ukrainian-children-into-enemies/

Ingram, Alan. 2001. Alexander Dugin: Geopolitics and Neo-Fascism in Post-Soviet Russia. Political Geography 20(8): 1029-1051.

Inosemzew, Wladislaw. 2022. Der Faschismus ist das, was folgt, nachdem sich der Kommunismus als Illusion erwiesen hat.‘ Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 10 March. https://www.nzz.ch/meinung/wladimir-putin-ist-ein-faschist-wie-er-im-lehrbuch-steht-ld.1673256.

Kailitz, Steffen, and Andreas Umland. 2016. “Why Fascists Took Over the Reichstag, But Did Not Capture the Kremlin: A Comparison of Weimar Germany and Post-Soviet Russia,” Nationalities Papers 45(2): 206-221.

Kailitz, Steffen, and Andreas Umland. 2019. “How Post-Imperial Democracies Die: A Comparison of Weimar Germany and Post-Soviet Russia.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 52(2): 105–115.

Kalinin, Kirill. 2019. “Neo-Eurasianism and the Russian Elite: The Irrelevance of Aleksandr Dugin’s Geopolitics.” Post-Soviet Affairs 35:5-6: 461-470.

Khel’vert [Höllwerth], Aleksandr [Alexander]. 2013. “Antiutopicheskii roman Den’ oprichnika Vladimira Sorokina i ‘Novaia oprichnina’ Aleksandra Dugina.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 10(2): 294-310.

Kochanek, Hildegard. 1998. Die Ethnienlehre Lev N. Gumilevs: Zu den Anfängen neu-rechter Ideologie-Entwicklung im spätkommunistischen Rußland, Osteuropa 48: 1184-1197.

Kozhevnikova, Galina, Anton Shekhovtsov, and Aleksandr Verkhovskii. 2009. Radikal’nyi russkii natsionalizm: Struktury, idei, litsa. Moskva: SOVA.

Kragh, Martin, Erik Andermo & Liliia Makashova. 2020. “Conspiracy Theories in Russian Security Thinking.” Journal of Strategic Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2020.1717954.

Kragh, M., & Umland, A. (2023). ‘Putinism beyond Putin: The political ideas of Nikolai Patrushev and Sergei Naryshkin in 2006–20.’ Post-Soviet Affairs, 39(5), 366–389.

Kragh, M., & Umland, A. (2024). Amerikas faschistisches Anti-Russland: Ukrainophobe Äußerungen Nikolai Patruschews 2014–2023. Zeitschrift für Politik 71(4): 351-367.

Kuzio, Taras. 2022a. Russian Nationalism and the Russian-Ukrainian War: Autocracy-Orthodoxy-Nationality. London: Routledge.

Kuzio, Taras. 2022b. ‘How Putin’s Russia embraced fascism while preaching anti-fascism,’ Atlantic Council, 17 April. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/how-putins-russia-embraced-fascism-while-preaching-anti-fascism/.

Laqueur, Walter. 1993. Black Hundred: The Rise of the Extreme Right in Russia. New York: HarperCollins.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. 2004. Ideologiya russkogo evraziistva ili Mysli o velichii imperii. Moskva: Natalis.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. ed. 2007a. Sovremennye interpretatsii russkogo natsionalizma. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. ed. 2007b. Russkii natsionalizm v politicheskom prostranstve: Issledovaniia po natsionalizmu v Rossii. Moskva: Franko-rossiiskii tsentr gumanitarnykh i obshchestvennykh nauk.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. ed. 2008. Russkii natsionalizm: Sotsial’nyi i kul’turnyi kontekst. Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. 2009a. Pereosmyslenie imperii v postsovetskom prostranstve: novaia evraziiskaia ideologiia. Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(1): 78-92.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. 2009b. Opyt sravnitel’nogo analiza teorii etnosa L’va Gumileva i zapadnykh novykh pravykh doktrin. Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(1): 189-200.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. 2009c. Aleksandr Dugin, ideologicheskii posrednik: sliianie razlichnykh doktrin pravoradikal’nogo politicheskogo spektra. Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(2): 63-87.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. 2009d. Aleksandr Panarin i ‘tsivilizatsionnyi natsionalizm’ v Rossii. Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(2): 143-158.

Lariuel’ [Laruelle], Marlen [Marlene]. 2015. Russkie natsionalisty i krainie pravye i ikh zapadnye sviazi: idoelogicheskie zaimstvovaniia i lichnye vzaimosviazi. Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 12(1): 325-342.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2004. “The Two Faces of Contempoary Eurasianism: An Imperial Version of Russian Nationalism.” Nationalities Papers 32(1): 115-136

Laruelle, Marlene. 2006. “Aleksandr Dugin: A Russian Version of the European Radical Right?” Kennan Institute Occasional Papers 294.

Laruelle, Marlene. ed. 2007. Le Rouge et le noir: Extrême droite et nationalisme en Russie, Paris: CNRS-Éditions.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2008. Russian Eurasianism: An Ideology of Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2009a. In the Name of the Nation: Nationalism and Politics in Contemporary Russia. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2009b. Inside and Around the Kremlin’s Black Box: The New Nationalist Think Tanks in Russia. Stockholm Paper des Institute for Security and Development Policy. www.isdp.eu/images/stories/isdp-main-pdf/2009_laruelle_inside-and-around-the-kremlinsblackbox.pdf.

Laruelle, Marlene. ed. 2009c. Russian Nationalism and the National Reassertion of Russia. London: Routledge.

Laruelle, Marlene. ed. 2012. Russian Nationalism, Foreign Policy and Identity Debates in Putin’s Russia: New Ideological Patterns after the Orange Revolution. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Laruelle, Marlene. Ed. 2015a. Eurasianism and the European Far Right: Reshaping the Europe-Russia Relationship. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2015b. “The Iuzhinskii Circle: Far-Right Metaphysics in the Soviet Underground and Its Legacy Today.” The Russian Review 74(4): 563-580.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2016a. “The Three Colors of Novorossiya, or the Russian Nationalist Mythmaking of the Ukrainian Crisis.” Post-Soviet Affairs 32(1): 55-74.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2016b. The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia. The Russian Review 75(4): 626–644.

Laruelle, M. (2021). Is Russia Fascist? Unraveling Propaganda East and West. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Laruelle, M. (2022). Is Russia Fascist?: A Response to Yoshiko Herrera, Mitchell Orenstein, and Anton Shekhovtsov. Nationalities Papers, 50(6), 1255–1258. doi:10.1017/nps.2022.82

Laruelle, M. (2024). Russland, Faschismus und Antifaschismus: Der Kampf um Europas Identität. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Laruelle, M. (2025). Ideology and Meaning-Making Under the Putin Regime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Likhachev, Viacheslav. 2002. Natsizm v Rossii. Moskva: Panorama, 2002.

Likhachev, Viacheslav, and Vladimir Pribylovskii, eds. 2005. Russkoe Natsional’noe Edinstvo 1990-2000, 2 vols. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Liuks [Luks], Leonid. 2009a. “Evraziiskaia ideologiia v evropeiskom kontekste.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(1): 39-56.

Liuks [Luks], Leonid. 2009b. “Evraziistvo i konservativnaia revoliutsiia: sobalzn antizapadnichestva v Rossii i Germanii.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(2): 5-22.

Luks, Leonid. 1986. “Die Ideologie der Eurasier im zeitgeschichtlichen Zusammenhang.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 34: 374-395.

Luks, Leonid. 2000. “Der ‘Dritte Weg’ der ‘neo-eurasischen’ Zeitschrift ‘Ėlementy’ – zurück ins Dritte Reich?” Studies in East European Thought 52(1-2): 49-71.

Luks Leonid. 2002. “Zum ‘geopolitischen’ Programm Aleksandr Dugins und der Zeitschrift Ėlementy – eine manichäische Versuchung.” Forum für osteuropäische Ideen- und Zeitgeschichte 6(1): 43-58.

Luks, Leonid. 2004. “Eurasien aus neototalitärer Sicht – Zur Renaissance einer Ideologie im heutigen Rußland.” Totalitarismus und Demokratie 1(1): 63-76.

Luks, Leonid. 2005. Der russische “Sonderweg”? Aufsätze zur neuesten Geschichte Rußlands im europäischen Kontext. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Luks, Leonid. 2008. “‘Weimar Russia?’ Notes on a Controversial Concept.” Russian Politics and Law 46(4): 47-65.

Luks, Leonid. 2009. Irreführende Parallelen: Das autoritäre Russland ist nicht faschistisch. Osteuropa 59 (4): 119–128.

Luks, Leonid. 2018. “Russlands „Konservative Revolution“? Die Eurasierbewegung und ihre Auseinandersetzung mit dem „Westen“ (1921–1938)”. Zivilisatorische Verortungen: Der “Westen” an der Jahrhundertwende (1880–1930), edited by Riccardo Bavaj and Martina Steber, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2018, pp. 112-124. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110529500-008

Mathyl, Markus. 1997/1998. “‘Die offenkundige Nisse und der rassenmäßige Feind’: Die National-Bolschewistische Partei (NBP) als Beispiel für die Radikalisierung des russischen Nationalismus.” Halbjahresschrift für südosteuropäische Geschichte, Literatur und Politik 9(2): 7-15; 10(1): 23-36.

Mathyl, Markus. 2000. “Das Entstehen einer nationalistischen Gegenkultur im Nachperestroika-Rußland.” Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung 9: 68-107.

Mathyl, Markus. 2002. “Der ‘unaufhaltsame Aufstieg’ des Aleksandr Dugin: Neo-Nationalbolschewismus und Neue Rechte in Russland.” Osteuropa 52(7): 885-900.

Mathyl, Markus. 2003. “The National-Bolshevik Party and Arctogaia: Two Neo-fascist Groupuscules in the Post-Soviet Political Space.” Patterns of Prejudice 36(3): 62-76.

McGlynn, J. (2023). Russian Propaganda Tactics in Wartime Ukraine, The Russia Program at George Washington University, 10, November. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xdmk4Mn2G-jNSWhljjuv7sCqMbE-LT3Y/view

McFaul, Michael. 2020. “Putin, Putinism, and the Domestic Determinants of Russian Foreign Policy.” International Security 45(2): 95-139.

Mikhailovskaia, Ekaterina, Vladimir Pribylovskii, and Aleksandr Verkhovskii. 1998. Natsionalizm i ksenofobiia v rossiiskom obshchestve. Moskva: Panorama.

Mikhailovskaia, Ekaterina, Vladimir Pribylovskii, and Aleksandr Verkhovskii. 1999. Politicheskaia ksenofobiia: Radikal’nye gruppy, predstavleniia liderov, rol’ tserkvi. Moskva: Panorama.

Mitrofanova, Anastasia V. 2005. The Politicization of Russian Orthodoxy: Actors and Ideas. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Mitrofanova, Anastasia. 2009. “Blesk i nishcheta neoevraziiskogo religiozno-politicheskogo proekta.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(1): 148-167.

Mitrokhin, Nikolay. 2015. Infiltration, Instruction, Invasion: Russia’s War in the Donbass. Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 1(1): 219-249.

Mitrokhin, Nikolay. 2019. Im Namen des Staates: Russische Nationalisten im Ukraine-Einsatz. Osteuropa 69(3-4): 103–121.

Moroz, Evgenii. 2010. “Evraziiskie metamorfozy: ot russkoi emigratsii k rossiiskoi elite.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 7(1): 15-45.

Motyl, A.J. 2007a. “Inside Track: Is Putin’s Russia Fascist?” The National Interest, 3 December. http://www.nationalinterest.org/Article.aspx?id=16258.

Motyl A.J. 2007b. “Post-Weimar Russia: Europe Faces the Destabilizing Implications of Russia’s Great-power Posturing,” IP-Journal, 1 July. https://ip-journal.dgap.org/en/ip-journal/regions/post-weimar-russia.

Motyl A.J. 2009. ‘Russland – Volk, Staat und Führer: Elemente eines faschistischen Systems,’ Osteuropa 59 (1): 109-124.

Motyl A.J. 2010. ‘Russia’s Systemic Transformations since Perestroika: From Totalitarianism to Authoritarianism to Democracy – to Fascism?’ The Harriman Review 17.2. pp. 1-14.

Motyl, A.J. 2015. „Is Putin’s Russia Fascist?” Atlantic Council, 23 April https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/is-putin-s-russia-fascist/.

Motyl, A.J. 2016. „Putin’s Russia as a Fascist Political System.” Communist and Post- Communist Studies 49(1): 25–36.

Motyl, A.J. (2022). National Questions: Theoretical Reflections on Nations and Nationalism in Eastern Europe. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Naarden, Bruno. 1996. “‘I am a genius, but no more than that’: Lev Gumilev (1912-1992), Ethnogenesis, the Russian Past and World History.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 44: 54-82.

Hanuš Nykl 2024. Ivan Ilyin: fascist or ideologue of the White Movement utopia? Studies in East European Thought 77(2):351-373

Oliinyk, A. (2023). The Military-Patriotic Infrastructure in Eastern Ukraine: Russian Proxy Republics (2014–2022). Oslo: Norwegian Defence University College. https://fhs.brage.unit.no/fhs-xmlui/handle/11250/3101161

Orenstein, M. A. (2022). Russia: Fascist or Conservative? Nationalities Papers, 50(6), 1245–1247. doi:10.1017/nps.2022.41

Østbø, Jardar. 2015. The New Third Rome: Readings of a Russian Nationalist Myth. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Pakhlevska, Oksana. 2011a. “Neoevrazizm, krizis russkoi identichnosti i Ukraina (Chast’ pervaia).” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 8(1): 49-86.

Pakhlevska, Oksana. 2011b. “Neoevrazizm, krizis russkoi identichnosti i Ukraina (Chast’ vtoraia).” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 8(2): 127-156.

Papp, Anatolii, Vladimir Pribylovskii, and Aleksandr Verkhovskii. 1996. Politicheskii ekstremizm v Rossii. Moskva: Panorama.

Paradowski, Ryszard. 1999. “The Eurasian Idea and Leo Gumilëv’s Scientific Ideology.” Canadian Slavonic Papers 41(1): 19-32.

Parland, Thomas. 2005. The Extreme Nationalist Threat in Russia: The Growing Influence of Western Rightist Ideas. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Plokhy, Serhii. 2018. Lost Kingdom: A History of Russian Nationalism from Ivan the Great to Vladimir Putin. London: Penguin.

Pribylovskii, Vladimir. 1995a. Russkie natsional-patriotichekie (etnokraticheskie) i pravoradikal’nye organizatsii: Kratkii slovar’-spravochnik. Moskva: Panorama.

Pribylovskii, Vladimir, ed. 1995b. Russkie natsionalisticheskie i pravoradikal’nye organizatsii, 1989-1995: Dokumenty i teksty. 1st Vol. Moskva: Panorama.

Pribylovskii, Vladimir, ed. 1995c. Vozhdi: Sbornik biografii rossiiskikh politicheskikh deyatelei natsionalistisicheskoi i impersko-patrioticheskoi orientatsii. Moskva: Panorama.

Pribylovskii, Vladimir, and Aleksandr Verkhovskii. 1995. Natsional-patrioticheskie organizatsii v Rossii: istoriia, ideologiia, ekstremistskie tendentsii. Moskva: Panorama.

Pribylovskii, Vladimir, and Aleksandr Verkhovskii. eds. 1997. Natsional-patrioticheskie organizatsii: kratkie spravki, dokumenty, i teksty. Moskva: Panorama.

Prozorov, Sergei, 2016. The Biopolitics of Stalinism: Ideology and Life in Soviet Socialism Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Putin, Vladimir. 2022. “Full text of Putin’s speech at annexation ceremony.” Mirage, 1 October. https://www.miragenews.com/full-text-of-putins-speech-at-annexation-866383/.

Pynnöniemi, K. (2021). ‘Ivan Ilʹin and the Kremlin’s Strategic Communication of Threats: Evil, Worthy and Hidden Enemies.’ In K. Pynnöniemi (Ed.), Nexus of Patriotism and Militarism in Russia: A Quest for Internal Cohesion. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. 81-110.

Rogachevskii, Andrei. 2004. Biographical and Critical Study of Russian Writer Eduard Limonov. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen.

Rossman, Vadim. 2002. Russian Intellectual Antisemitism in the Post-Communist Era. Lincoln, NE: The University of Nebraska Press.

Rossman, Vadim. 2009. “V poiskakh russkoi idei: platonizm i evraziistvo.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(1): 57-77.

Sainakov, Nikolai, and Ilia Iablokov. 2011. “Teorii zagovora kak chast’ marginal’nogo diskursa (na primere sozdatelei Novoi khronologii N.A. Morozova i A.T. Fomenko).” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 8(1): 148-158.

Schlacks, Jr., Charles, and Ilya Vinkovetsky, eds. 1996. Exodus to the East: Forebodings and Events. An Affirmation of the Eurasians. Idyllwild, CA: Charles Schlacks, Jr.

Sedgwick, Mark. 2004. Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Senderov, Valerii. 2009a. “Neoevraziistvo: real’nost, opasnosti, perspektivy.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(1): 105-124.

Senderov, Valerii. 2009b. “Konservativnaia revoliutsiia v postsovetskom izvode: kratkii ocherk osnovnykh idei.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 6(2): 41-62.

Shekhovtsov, A. 2008 „The Palingenetic Thrust of Russian Neo-Eurasianism: Ideas of Rebirth in Aleksandr Dugin’s Worldview.” Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 9, Nr. 4 (2008): 491–506.

Shekhovtsov, A. 2009. „Aleksandr Dugin’s New Eurasianism: The New Right à la russe.” Religion Compass 3–4: 697–716.

Shekhovtsov, A. 2014. „Putin’s Brain?“ New Eastern Europe, no. 4 (XII): 72-79

Shekhovtsov, Anton. 2015. „Aleksandr Dugin and the West European New Right, 1989–1994.” In Eurasianism and the European Far Righ, hrsg. v. Marlene Laruelle, 35–54. Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2015.

Shekhovtsov, A. 2017a. Russia and the Western Far Right: Tango Noir. London: Routledge.

Shekhovtsov, A. 2017b. „Aleksander Dugin’s Neo-Eurasianism and the Russian-Ukrainian War,” in: Mark Bassin and Gonzalo Pozo, eds., The Politics of Eurasianism: Identity, Popular Culture and Russia’s Foreign Policy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield

Shekhovtsov, A. (2022). What Happens When Soft Power Fails. Nationalities Papers, 50(6), 1252–1254. doi:10.1017/nps.2021.111

Shekhovtsov, Anton, and Andreas Umland. 2009. „Is Dugin a Traditionalist? ‘Neo-Eurasianism’ and Perennial Philosophy.” Russian Review 68: 662–678.

Shenfield, Stephen D. 1998. „The Weimar/Russia Comparison: Reflections on Hanson and Kopstein.” Post- Soviet Affairs 14,4: 355–368.

Shenfield, Stephen D. 2001. Russian Fascism: Traditions, Tendencies and Movements. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Sineokaya, Y. (2024). Between fascism and bolshevism: How Alexander Dugin came to head the ‘Ivan Ilyin Higher School of Politics,’ The Insider, 7 June. https://theins.ru/en/opinion/yulia-sineokaya/272221

Snegovaya, Maria. 2019. “What Factors Contribute to the Aggressive Foreign Policy of Russian Leaders?” Problems of Post-Communism 67 (1): 93-110.

Snegovaya, Maria. 2020. “Guns to Butter: Sociotropic Concerns and Foreign Policy Preferences in Russia.” Post-Soviet Affairs, April 12. DOI: 10.1080/1060586X.2020.1750912 (accessed June 16, 2020).

Snyder, Timothy. 2018a. The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. New York, NY: Tim Duggan Books.

Snyder, T. 2018b. “Ivan Ilyin, Putin’s Philosopher of Russian Fascism,” The New York Review of Books, 16 March. https://www.nybooks.com/online/2018/03/16/ivan-ilyin-putins-philosopher-of-russian-fascism/

Snyder, T. 2022. “We Should Say It. Russia Is Fascist,” The New York Times, 19 May 2022 https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/19/opinion/russia-fascism-ukraine-putin.html

Taylor, Brian D. 2018. The Code of Putinism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Torbakov, Igor. 2018. After Empire: Nationalist Imagination and Symbolic Politics in Russia and Eurasia in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Century. Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

Straus, Ira. 2022. ‘Is Russia Fascist?’ The Globalist, 5 July. https://www.theglobalist.com/is-russia-fascist/

Umland, Andreas. 2004. „Some Addenda on the Relevance of Extremely Right-Wing Ideas in Putin’s New Russia.” Erwägen, Wissen, Ethik 15 (4): 591–593.

Umland, Andreas. 2005a. „Classification, Julius Evola and the Nature of Dugin’s Ideology.” Erwägen, Wissen, Ethik 16 (4): 566–569.

Umland, Andreas. 2005b. „Concepts of Fascism in Contemporary Russia and the West.” Political Studies Review 3 (1): 34–49.

Umland, Andreas. 2008a. ‘Is Putin’s Russia Really “Fascist”? A Response to Alexander Motyl,’ Zeithistorische Streitfragen, 17 January. http://www1.ku-eichstaett.de/ZIMOS/streitfragen.html#4

Umland, Andreas. 2008b. „Zhirinovsky’s Last Thrust to the South and the Definition of Fascism.” Russian Politics and Law 46(4): 31–46.

Umland, Andreas. 2009. “Restauratives versus revolutionäres imperiales Denken im Elitendiskurs des postsowjetischen Russlands: Eine spektralanalytische Interpretation der antiwestlichen Wende in der Putinschen Außenpolitik.” Forum für osteuropäische Ideen- und Zeitgeschichte 13(1): 101-125.

Umland, Andreas. 2010a. „Aleksandr Dugin’s Transformation from a Lunatic Fringe Figure into a Mainstream Political Publicist, 1980–1998: A Case Study in the Rise of Late and Post- Soviet Russian Fascism.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 1 (2): 144–152.

Umland, Andreas. 2010b. Stalin’s Russocentrism in Historical and International Context. Nationalities Papers 38(5): 741-748.

Umland, Andreas. 2014. “Das eurasische Reich Dugins und Putins: Ähnlichkeiten und Unterschiede.” Kritiknetz: Zeitschrift für Kritische Theorie der Gesellschaft, 26 June, http://www.kritiknetz.de/images/stories/texte/Umland_Dugin_Putin.pdf (accessed December 7th, 2016).

Umland, Andreas. 2015. „Challenges and Promises of Comparative Research into Post- Soviet Fascism: Methodological and Conceptual Issues in the Study of the Contemporary East European Extreme Right.” Communist and Post- Communist Studies 28 (2–3): 169–181.

Umland, Andreas. 2017. “Post-Soviet Neo-Eurasianism, the Putin System, and the Contemporary European Extreme Right.” Perspectives on Politics 15 (2): 465–476.

Umland, Andreas. 2018. “Restavratsionnyi i revoliutsionnyi imperializm v politicheskom diskurse Rossii: Sdvig postsovetskogo ideologicheskogo spektra vpravo i antizapadnyi povorot Kremlia.” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 15(1-2): 7-28.

Umland, Andreas. 2023. “Historische Esoterik als Erkenntnismethode: Wie russische Pseudo-Wissenschaftler zu Moskaus antiwestlicher Wende beigetragen haben,” Sirius: Zeitschrift für Strategische Analysen 7(1): 3–10.