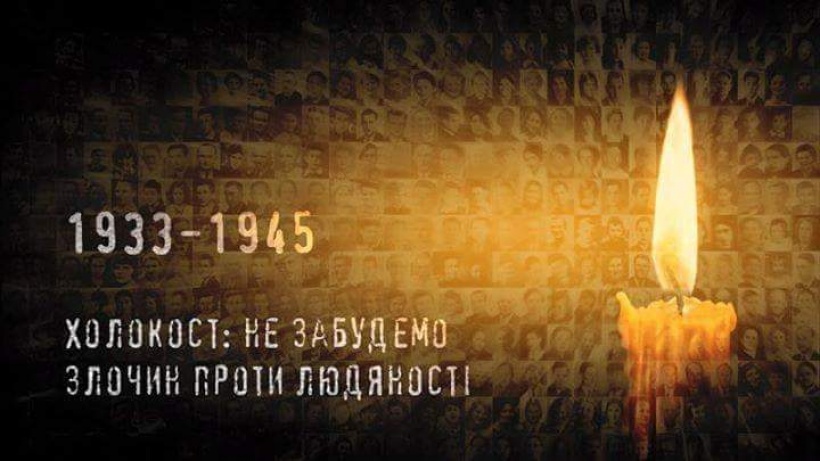

Holocaust Memorial Day – 2022

To mark Holocaust Memorial Day, we publish two texts on the massacre at the Babyn Yar ravine on the edge of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv. The largest single mass shooting of Jews in German-occupied Europe.

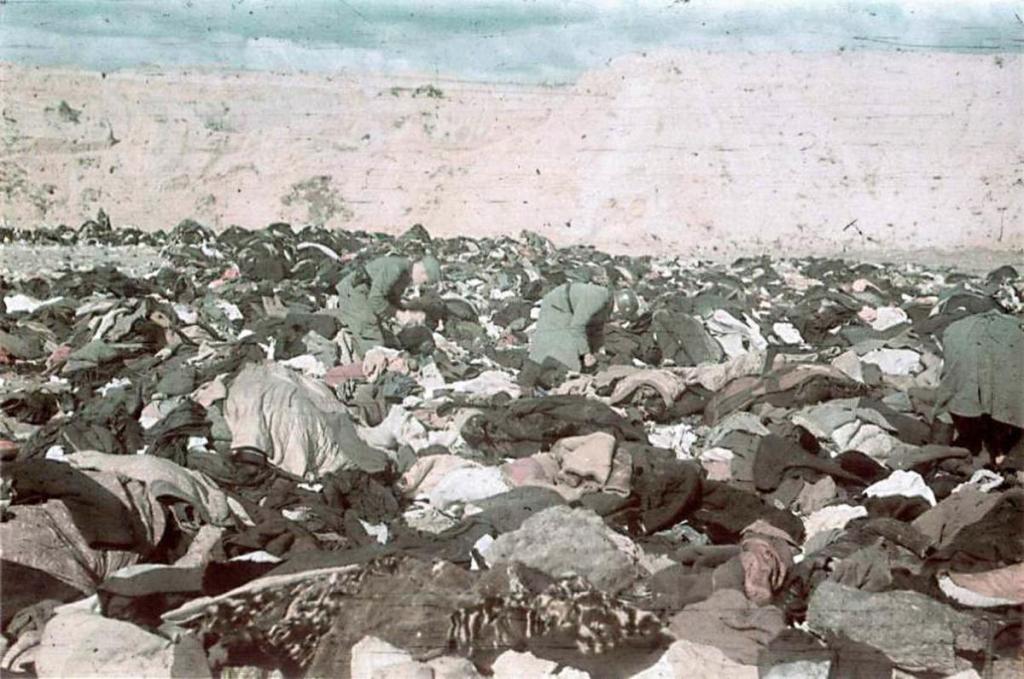

The initial phase of the killings occurred between September – November 1941. The first of the massacres was of Kyiv’s Jews on 29-30 September 1941. The killing only stopped when the Nazi’s were driven from Kyiv on 4 November 1943. An estimated 150,000 people were murdered at Babyn Yar under the German occupation, it has become a symbol of the ‘Holocaust by Bullets’.

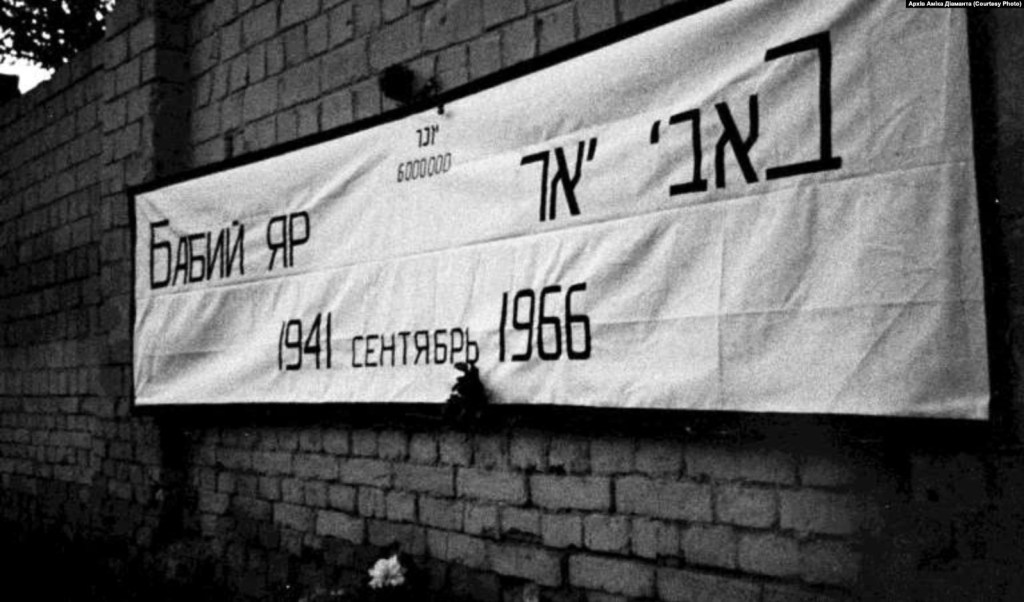

Published below is a full English translation of the important speech and the postscript, by the Ukrainian Marxist dissident Ivan Dzyuba author of the classic book Internationalism or Russification. Dzyuba, originally from Donetsk Oblast was a leading writer and fighter for greater freedom and cultural rights. Dzyuba made his speech on September 29, 1966, the 25th Anniversary of the massacre and the first memorial event in Kyiv to honour the victims. Organised by Jewish and Ukrainian activists the event turned the tide as regards historical recognition of the Babyn Yar massacre after decades of official silence and anti-Semitism.

Opposite on the website we publish an article by socialist historian Christopher Ford on Anti-Semitism, Fascism, Stalinism and Holocaust Memory which examines the massacre at Babyn Yar and the struggles for historical recognition in the years after liberation from the Nazi’s.

Ivan Dzyuba Address at Babyn Yar

Postscript by Ivan Dzyuba to the publication of the speech in Babyn Yar on 29 September 1966

It was in the last ten days of September 1966 that Viktor Nekrasov passed me a message through friends asking me to come to his house before 1 pm on 29 September. I guessed what this was about. After all, 29 September was a special day in the life of many Kyivans. On that day some Kyivans took bouquets of flowers with verses of mourning to that edge of the city, the name of which is sadly remembered throughout the world: Babyn Yar. Other Kyivans on that same day racked their brains about how to prevent a large gathering of the first group in that place. And a third group of Kyivans acting on the orders of the second group zealously stalked the first group and “took measures” if they needed to against the most agitated among them.

However, 29 September 1966 was not just the next anniversary of the beginning of the Babyn Yar tragedy, but its 25th anniversary. A quarter century of grief remembered, whose remembrance was explicitly prohibited, unwanted and manicious as far as the authorities were concerned, a stance reinforced by the government unleashing a programme of public works to change the actual topography of Babyn Yar.

I was in Viktor Platonovych’s home at the specified time. There I saw his friends from the Kyiv Studio of Scientific and Popular Cinematography. Led by Heli Snehirov, they were getting ready to film something: they were expecting more people than usual to be there. If the gathering was not banned it would be given at least some form of ritual. When we got to Babyn Yar we were struck by what we saw there. All the surrounding hillocks and parks were covered by many people in distinct groups – thousands and thousands of people. Yet this unco-ordinated element was here as a single living being. Suffering had set onto their faces while people’s eyes seemed out of place and time. They were looking into the depths of time and they saw the frightening picture of what had not and would never become the past for them. The shadow of horror long ago and some kind of human loss of way hung over Babyn Yar. Thousands of people, silent and immobilised in the tumult, embodied the muted cries of a whole people.

People were silent but this was an insistently questioning silence. People wanted to listen, listen and hear something important said. So when word got around that “writers have arrived”, people converged on us, pulled us apart in different directions. Everyone (Borys Dmytrovych Antonenko Davydovych had joined us on his own initiative) was surrounded by a tight crowd who demanded “Say something, at least something!” One had to improvise, though we spoke about what we well knew and was hurting inside.

– Babyn Yar – “September 1941-1966,” “Remember the Six Million.”

Someone taped our speeches and in a few days they appeared in samizdat, then in its infancy. Naturally “the powers that be” demonstrated they thoroughness and “militancy”, applying “educational” and administrative measures to those who had transgressed. The first victims were the cinematography studio workers. The film they took was confiscated and they were punished by various fines. My speech at Babyn Yar was added to the “criminal evidence” against me that the KGB had already gathered.

Translation by Marko Bojcun

Babyn Yar Address by Ivan Dzyuba

There are events, tragedies the enormity of which make all words futile and of which silence tells incomparably more—the awesome silence of thousands of people. Perhaps we, too, should keep silent and only meditate. But silence says a lot only when everything that could have been said has already been said. If there is still much to say, or ifnothing has yet been said, then silence becomes a partner to falsehood and enslavement. We must therefore speak and continue to speak wherever we can, taking advantage of all opportunities, [for they] come so infrequently.

I want to say a few words—one-thousandth of what I am now thinking and what I would like to say here. I want to address you as men—as my brothers in humanity. I want to address you Jews as a Ukrainian—as a member of the Ukrainian nation to which I proudly belong.

Babyn Yar is a tragedy of all mankind, but it happened on Ukrainian soil. And therefore, a Ukrainian has no right to forget it anymore than a Jew. Babyn Yar is our common tragedy, a tragedy for both the Jewish and Ukrainian nations.

This tragedy was brought on our nations by fascism.

Yet one must not forget that fascism [could] neither begin nor end in Babyn Yar. Fascism begins in disrespect to man, and ends in the destruction of man, in the destruction of nations—though not necessarily in the manner of Babyn Yar.

Let us imagine for a moment that Hitler had won, that German fascism had been victorious. One can be sure that the victors would have created a brilliant and “flourishing” society which would have attained a high level of economic and technical development and made all the same scientific and other discoveries that we have made. Probably the mute slaves of fascism would eventually have “tamed” the cosmos and flown to other planets to represent humanity and earthly civilization. Moreover, this regime would have done everything in order to consolidate its own “truth” so that men would forget the price they paid for such “progress,” so that history would excuse or forget their enormous crimes, so that their inhuman society would seem normal to people and even the best in the world. And then, not on the ruins of the Bastille, but on the desecrated forgotten sites of national tragedy, thickly choked with sand, there would have been an official sign: “Dancing Here Tonight.”

We should therefore judge each society not by its external technical achievements but by the position and meaning it gives to man, by the value it puts on human dignity and human conscience.

Today in Babyn Yar we commemorate not only those who died here. We commemorate millions of Soviet warriors—our fathers—who gave their lives in the struggle against fascism. We commemorate the sacrifices and efforts of millions of Soviet citizens of all nationalities who unselfishly contributed to the victory over fascism. We should remember this so that we may be worthy of their memory, and of the duty which has been imposed upon us by the countless human sacrifices, hopes, and aspirations that were made.

Are we worthy of this memory? Apparently not, since even now various forms of human hatred ‘are found among us— [including one] we call by the worn-out, banal, and yet so terrible [name], antisemitism. Antisemitism is an “international” phenomenon. It has existed and still exists in all societies. Sadly enough, our own society is also not free of it. Perhaps there is nothing strange about this —after all, antisemitism is the fruit and companion of age-old barbarism and slavery, the foremost and inevitable result of political despotism. To conquer it — in entire societies—is not an easy task, nor can it be done quickly. But what is strange is the fact that no struggle has been waged here against it during the post war decades; what is more, it has often been artificially nourished. It seems that Lenin’s instructions concerning the “struggle against antisemitism are forgotten in the same way as his precepts regarding national development of the Ukraine.

In Stalin’s day, there were open and flagrant attempts to use prejudices as a means of playing off Ukrainians and Jews against each other—to limit the Jewish national culture on the pretext of Jewish bourgeois nationalism, Zionism, and so on, and to suppress the Ukrainian national culture on the pretext of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism. These cunningly prepared campaigns wrought damage on both nationalities and did nothing to further friendship between them. They only added one more sad memory to the harsh history of both nations and to the complex history of their relationship.

We must return to these memories, not in order to open old wounds, but in order to heal them once and for all.

As a Ukrainian, I am ashamed that, as in other nations, there is antisemitism here; that those shameful phenomena which we call antisemitism— [and which are] unworthy of mankind—exist here.

We Ukrainians must fight in our midst against all manifestations of antisemitism or disrespect towards the Jews…

You Jews must fight against those in your midst who do not respect the Ukrainian people, the Ukrainian culture, the Ukrainian language—against those who unjustly see a potential antisemite in every Ukrainian.

We must outgrow all forms of human hatred, overcome all misunderstandings, and by our own efforts win true brotherhood.

It would seem that we ought to be the two nations most likely to understand each other, most likely to give mankind an example of brotherly cooperation. The history of our nations is so similar in its tragedies that, in the Biblical motifs of his “Moses,” Ivan Franko recreated the story of the Ukrainian nation in terms of the Jewish legend. Lesia Ukrainka began one of her best poems about Ukraine’s tragedy with the line: “And you fought once, like Israel. . . .”

Great sons of both our nations bequeathed to us mutual understanding and friendship. The lives of the three greatest Jewish writers—Sholom Aleykhem, Itskhok Peretz, and Mendele Moykher-Sforim—are bound up with Ukraine. . . . The brilliant Jewish publicist, Vladimir Zhabotinsky, fought on the Ukrainian side in Ukraine’s struggle against Russian Tsarism and called upon the Jewish intelligentsia to support the Ukrainian national liberation movement and Ukrainian culture.

One of Taras Shevchenko’s last civic acts was his well-known protest against the antisemitic policies of the Tsarist government. Lesia Ukrainka, Ivan Franko, Boris Hrinchenko, Stepan Vasylenko, and other leading Ukrainian writers well knew and highly valued the greatness of Jewish history and of the Jewish spirit, and they wrote of the suffering of the Jewish poor with sincere sympathy.

Our common past consists not only of blind enmity and bitter misunderstanding—although there was much of this, too. Our past also shows examples of courageous solidarity and cooperation in the fight for our common ideals of freedom and justice, for the well-being of our nations.

We, the present generation, should continue this tradition, and not the tradition of distrust and reserve.

But sadly enough, there are a number of factors which are not conducive to letting this noble tradition of solidarity take firm root.

One of these factors is the lack of openness and publicity given to the nationalities question. As a result, a kind of “conspiracy of silence” surrounds the problem. The attitude in socialist Poland could serve as a good example for us. We know how complicated the relations between Jews and Poles were in the past. Now there are no traces of past ill-feeling. What is the “secret” of this success? In the first place, the Poles and the Jews were brought closer together by the common evil of the Second World War. But we, too, had this evil in common.

Secondly—and this we do not have—in socialist Poland relations between nationalities are the subject of scientific sociological study, public discussion, inquiries in the press and literature, and so on. All of this creates a proper atmosphere for successful national and international enlightenment.

We, too, should care about and exert ourselves—in deed rather than just in word—on behalf of this kind of enlightenment. We must not ignore antisemitism, chauvinism, disrespect towards any nationality, a boorish attitude toward any national culture or national language. There is plenty of boorishness in our midst, and in many of us it begins with the rejection of ourselves—of our nationality, culture, history, and language—even though such a rejection is not always voluntary nor the person involved to be blamed.

The road to true and honest brotherhood lies not in self-oblivion, but in self-awareness; not in rejection of ourselves and adaptation to others, but in being ourselves and respecting others. The Jews have a right to be Jews and the Ukrainians have a right to be Ukrainians in the full and profound, not merely the formal, sense of the word. Let the Jews know Jewish history, the Jewish culture and the Yiddish language, and be proud of them. Let the Ukrainians know Ukrainian history, the Ukrainian culture and language, and be proud of them. Let them also know each other’s history and culture and the history and culture of other nations, and let them know how to value themselves and others—as brothers.

It is difficult to achieve this—but better to strive for it than to shrug one’s shoulders and swim with the current of assimilation and adaptation, which will bring about nothing except boorishness, blasphemy, and veiled human hatred.

With our very lives we should oppose civilized [forms of] hatred for mankind and social boorishness. There is nothing more important for us at the present time, because without such opposition all our social ideals will lose their meaning.

This is our duty to millions of victims of despotism; this is our duty to the better men and women of the Ukrainian and Jewish nations who have urged us to mutual understanding and friendship; this our duty to our Ukrainian land in which we live together; this is our duty to humanity.

(Address by I. Dzyuba, Sept. 29, 1966)