Antisemitism and the struggle for historical recognition

By Christopher Ford

Babyn Yar is a ravine in Kyiv, a site of massacres carried out by Nazi Germany’s forces during its campaign against the Soviet Union in World War 2. The first massacre took place on 29-30 September 1941, with over 33,000 Jewish people murdered. Other victims of massacres at the site included Romani people, left-wing political activists and Soviet prisoners of war. It is estimated that well over 100,000 people were murdered there during the German occupation. Below Christopher Ford tells the story.

Nazi Germany and Romania invaded the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukrainian SSR) on 22 June 1941, by November virtually all of Ukraine was under German occupation. The territory of Ukraine was partitioned into five administrative areas, the experience of Ukrainian would vary greatly between the areas of occupation. The region of Galicia was annexed to the Generalgouvernement, northern Bukovyna and Transnistria to Romania. These territories were to experience different degrees of brutality in comparison to the sixteen million people, including Kyiv, governed by the Reichskommissariat Ukraine at whose head was Reichskommissar Erich Koch.

Appointed by Hitler, Koch viewed Ukrainians as an inferior race and oversaw the plunder of agriculture and industry carried through with a reign of terror which cost millions of lives. It is estimated between 3 to 5 million Ostarbeiter forced labourers were transported to Germany, over fifty per-cent were from Ukraine. Those who remained were exploited under a draconian labour regime, principally to supply food to sustain the German war economy. Koch declared that ‘in view of this task feeding of the Ukrainian civilian population is of absolutely no concern’. The Nazis set as their goal the ‘destruction of the unnecessary mouths (Jews), and residents of big Ukrainian cities, such as Kyiv’, they set out to achieve this by starvation rations and acts of mass murder. John-Paul Himka in his study Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust notes that ‘One quarter of all Holocaust victims lived on the territory that now forms Ukraine’, the killing of Ukrainian Jews began almost immediately with the invasion. The most infamous would be in Kyiv – the city would lose sixty per cent of its population during Nazi rule.

The German Occupation of Kyiv 1941

The German occupation of Kyiv began on 19 September 1941, when units of the Wehrmacht and SS entered the city. They were soon joined by Sonderkommando from the notorious Einsatzgruppe killing squads, who began operating with the permission of the German Sixth Army, and by a Schutzspolizei, German Police Battalion.

A tiny minority of the populace, those “politically reliable” supporters provided considerable assistance to the occupation, forming a Kyiv City administration with a multi-ethnic Ukrainian Police Force under German supervision. A key role in this was played by the Western Ukrainian based Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, particularly the wing aligned with Andrii Melnyk, OUN-M who were rivalled by the OUN-B led by Stepan Bandera. However, both factions of OUN collaborated with the German’s, enrolled in the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police and participated in the perpetration of the Nazi crimes in Ukraine.

The eminent Ukrainian historian Ivan Rudnytsky noted that during the occupation: “It is a fact, however that the Ukrainian nationalist underground never raised its voice against the slaughter of the Jews. There are situations when silence is morally indefensible, when it amounts to a complicity.”

Leading activists of OUN-M such as Bohdan Onufryk (Konyk) and Ivan Kedulych, and also members of OUN-B such as Dmytro Myron(Orlik), and others also from Nationalist militia’s in Western Ukraine travelled to Kyiv, and helped form the German proxy administration and Ukrainian Police in the city. The force comprised not only Ukrainians, also Russians, many rogue elements, criminals, opportunists and former POW’s. It took part in arrests, guarding prison camps, executions and deportations of forced labour to Germany. Those Nationalists who collaborated provided translators and support for the Sonderkommando in the mass killings at Babyn Yar, witnesses recalled their blue and yellow flag flying from a building on Yaroslaviv Val Street as Jews were rounded up. There is conflicting evidence as to whether the Ukrainian Police participated in the actual shootings at Babyn Yar, the author Anatoly Kuznetsov in Kyiv at the time insists the Police participated.

There were 200,000 Jewish inhabitants of Kyiv when the German’s invaded, many had left the city before it was occupied, most Jewish men were in the armed forces or evacuated before the advancing Germans. Those left behind were largely the elderly, woman and children. At the time knowledge of the Nazi’s was scant, in the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact their persecution of the Jews was not publicised by state media. Furthermore, there was a lack of trust in Stalinist propaganda. As such before the Germans arrived Kyiv’s Jews were ill prepared for what would happen to them. For this the Stalinist authorities hold significant responsibility.

What remained of the Jewish populace were quickly subject to persecution by the Wehrmacht, who forced Jews to start clearing the battle-damaged city, those of ‘draft age’ were detained in labour camps.

The persecution turned to genocide when on 23 and 24 September mines hidden by retreating Red Army troops were exploded in the main street Khreshchatyk and parts of the city centre. The sabotage killed hundreds of German soldiers and officers; it was used as a pretext by the Germans to commence the mass murder of all Jews in Kyiv.

The decision was taken at a meeting attended by SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln, the commander of Einsatzgruppe C, SS-Brigadeführer Dr Otto Rasch, the commander of Sonderkommando 4a and SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel. It is believed that SS-Brigadfuhrer Kurt Eberhardt with command over Kyiv and Wehrmacht General Hans Von Obstfelder also attended. It is highly likely it was the commander of the German Sixth Army Field Marshal General Walther von Reichenau who approved the mass murder at Babyn Yar on 25 September. On the same day Wehrmacht units were ordered to prevent all Jews from leaving Kyiv.

The mass murder could not have been carried out without the assistance of the German Sixth Army, which would be mythologised by some historians for their role at the Battle of Stalingrad. Their crimes in Kyiv and other parts of Ukraine is too often overlooked because some officers later joined Moscow’s sponsored National Committee for a Free Germany. The same Sixth Army had allocated 100,000 bullets to the SS and Police for the murder of Jews at Babyn Yar.

The first killings began on 27-28 September when Jewish civilians arrested by the Wehrmacht and Sonderkommando patrols were shot along with Jewish POWs at the Dulag 201 prison camp in Kyiv.

On 27 September the Sixth Army printed two-thousand notices which were posted by the Ukrainian Police around Kyiv ordering Jews to assemble on 29 September, simultaneously a rumour was spread they were to be resettled.

The announcement in Russian, Ukrainian and German stated:

‘All the Yids of the city of Kyiv and its vicinity must appear on Monday 29 September, 1941 by 8 a.m. at the corner of Melnikova and Dokhterivskaya streets (next to the cemetery). Bring documents, money and valuables, and also warm clothing, bed linen etc. Any Yids who do not follow this order and are found elsewhere will be shot. Any civilians who enter the dwellings left by Yids and appropriate the things in them will be shot’.

Tens of thousands of people were forced to march along the “road of death” to Babyn Yar, there they were forced to undress, and their belongings stolen, the barbarity which followed was described by Kuno Callsen former member of Sonderkommando 4a at his trial in 1967:

The Jews were forced to descend the slope to the bottom of the ravine. They had to lie down there. We marksmen stood behind the Jews and had to shoot them with submachine-guns from behind. There were no volleys but continuous single shots from submachine-guns. When one layer had filled the [width of] the pit, the next Jews had to lie down on top of the first layer. I had to shoot for some time and then for some time to load my magazines. I also brought the Jews. When the Jews were standing at the edge of the pit, they saw what was going on in the pit. They cried loudly and threw themselves readily into the pit to meet their death.

………I can remember mothers lying on top of their small children to protect them from death. What we had to experience was too much for any human being. When the layers rose higher, we had to trample down the bodies. Our boots were spattered with blood; it was horrible to feel the bodies under our boots. I wracked my brain wondering how I was capable of this, of enduring this whole process. Today I have no explanation for this.

Kuno Callsen former member of Sonderkommando 4a

On the first day of the massacre, 22,000 people were murdered. The terrified people who were not shot that day were locked up in nearby garages, the next day 12,000 more people were killed. In total, the German’s murdered 33,771 people in two days. The edges of the ravine were then blown up to cover the bodies, Red Army prisoners made to level the surface of the mass grave.

After the massacre the City administration published an order in Kyiv’s only newspaper Ukraïnske Slovo (Ukrainian Word) edited by Ivan Rohach a member of OUN-M, for lists of belongings left in apartments to be made of the Jews who had ‘left’ the city. This same paper had branded Jews ‘the greatest enemy’ who deserved no mercy. The Ukrainian Police are known to have engaged in widespread theft from the empty apartments.

After the massacre – solidarity and collaboration

The populace of Kyiv, like the victims themselves, did not know immediately that a massacre was to occur. But the truth quickly became apparent. Indeed, some individuals had gone to Babyn Yar to say goodbye to friends and neighbours, discovering the reality and narrowly escaped. The massacre was followed by a campaign to instil fear in any who would help surviving Jews. The Ukrainian Police issued a decree that hiding Jews was punishable by death, housing managers were obliged to inform on any Jewish residents. The German commandant and Ukraïnske Slovo demanded residents denounce Jews hiding and praised those ‘true patriots’ informing the Gestapo.

There were many who did help survivors and others whether through fear, opportunism or bigotry turned informer. After the war high ranking Nazi Erich Ehrlinge stated that executions continued of hundreds of Jews still hiding, the ‘number of denunciations was so large that the office was unable to process them all due to the lack of personnel.’ The Ukrainian writer Dokiya Humenna then living in the city claimed: ‘There was not a person in Kyiv who did not abhor, who inwardly did not shudder at Hitler’s butchery of the Jews’. There is certainly a degree of overstatement in her recollection, but it is not entirely without truth, there are numerous accounts of even those with bigoted views horrified at the reality of mass murder.

In Kyiv as in other parts of Soviet Ukraine, the Nazi’s were not as successful in whipping up sections of the populace to antisemitic violence in contrast to former Polish ruled Ukrainian territory in the west. (In which the OUN played their own role). Various accounts record a profound change of attitude towards the Germans after Babyn Yar, people began to predict they would now face a similar fate as the Jews. The German officer Theodor Oberländer himself a vicious antisemite, bemoaned in October 1941 the Wehrmacht was forfeiting the sympathy of the inhabitants.

Mass murder continues

Throughout October 1941 the shootings continued, Jews who had been in hiding were killed, on 18 October 300 Jewish patients of the St. Cyril psychiatric hospital were shot, a total of 785 patients were killed by 1942. Over 900 civilian hostages were killed in October-November 1941 in retribution for alleged sabotage. From mid-October the Nazis began killing the Roma, captured sailors of the Dnieper flotilla and members of the communist underground.

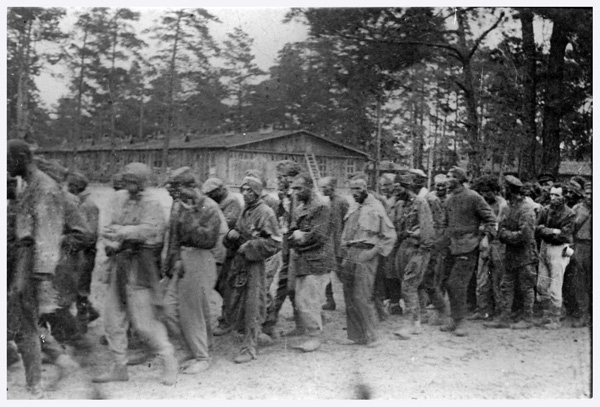

Prisoners of War held in appalling conditions at Darnytsia were also subject to systematic shootings, from October 1941- March 1942, over 500 Jewish POW’s and 1,500 commanders and political workers were shot. At the camp itself it is estimated 20,000 died overall.

The second stage of mass executions occurred at the end of winter 1942 to mid-August 1943. The killings included many of the three thousand prisoners of the Syrets concentration camp, a few hundred meters from Babyn Yar ravine, mostly POW’s, suspected underground and partisans, surviving Jews and Ukrainian Nationalists. Their bodies were buried in pits at Babyn Yar and near the camp. During this period the Nazis are known to have killed 617 members of the Communist underground, among them 129 women, also buried at Babyn Yar.

In a final act of barbarity, the last stage of killings took place in August-September 1943 when ‘Operation 1005’ began in Kyiv. Prisoners from Poltava interned at the Syretsk camp along with 100 remaining Jewish prisoners were chained in shackles and forced to dig up thousands of corpses, wood from fences and gravestones from the nearby Jewish cemetery was used to make pyres to burn them.

The prisoners rebelled and attempted to escape, only eighteen succeeded, and survived to testify to what they had seen, among them was Zakhar Trubakov, who recalled:

‘Only when I found myself beyond the fence, in relative safety, I thought that if I should stay alive I must remember the date: September 29, 1943. Much later, after the war, I was surprised to recollect that it was exactly two years before our daring escape – on September 29, 1941, – that the murders of Jews in Babyn Yar had begun’

The remaining prisoners were themselves shot and burned. On 6 November 1943 troops of the 1st Ukrainian Front and red partisans liberated Kyiv from the Nazis – ending the killing at Babyn Yar.

The German occupation of Kyiv had lasted just over two years, according to various estimates in that time they murdered between 100,000 – 150,000 people at Babyn Yar. It included Jews, Ukrainians, Roma, Russians, Karaim and many others. Vitaliy Nakhmanovych of the Museum of History of Kyiv estimates up to 70,000 of the victims were Jews.

From today’s vantage point when we consider how many were required to carry out such a scale of murder, it is difficult to accept the victims received adequate justice or historical recognition.

Post war justice eludes Babyn Yar

According to the historian Franziska Davies 700 men were directly involved in the actual killing in September 1941 – a mere 10 have been convicted.

After the war nobody from the Wehrmacht was ever put on trial for the Babyn Yar massacre, despite the Sixth Army surrender at Stalingrad (to a Ukrainian general) and other of its former commanders captured in the West.

At the Nuremberg trials only SS Standartenführer Paul Blobel who led the Sonderkommando, was sentenced to death and hanged for crimes at Babyn Yar. Otto Rasch who commanded Einsatzgruppe C died in custody. In 1967 five members of the Sonderkommando were sentenced in Germany to various terms in prison.

It has been alleged the British government refused to extradite Reichskommissar Erich Koch, to the USSR. Whether it is true or not, he was deported to Poland in 1950, eventually in 1959 he was sentenced to death for crimes in occupied Poland. Koch was never charged for his crimes in Ukraine. Shockingly, due to ill health Koch’s sentence was commuted to life in prison, in 1986 he died unrepentant in prison. Inexplicably the USSR did not insist the death sentence be implemented or he be extradited to face trial in the Ukrainian SSR.

The Commandant of the Ukrainian Police in Kyiv, Ivan Kedyulych fled when the Nazi’s turned on their OUN collaborators, he escaped the Gestapo and became a commander of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in Western Ukraine. Today Kedyulych has streets in Perechyn and in Khust named in his honour and is celebrated as a ‘hero’ of the UPA.

Volodymyr Bagaziy, a member of OUN-M was Deputy Mayor (Buergermeister) of Kyiv, and from October 1941 was Mayor. Present at the Babyn Yar massacre, Bagaziy was himself arrested in 1942 and shot at Babyn Yar. Despite being a Nazi collaborator, in July 2021 a memorial service was held in his honour, along with Rohach and other 621 known OUN members buried at Babyn Yar. An NGO linked to the German Embassy proposed a stumbling block (Stolperstein) in his memory – thankfully it has not happened.

On 17-28 January 1946 the massacre at Babyn Yar became prominent during the public trial in Kyiv of individuals representing the Wehrmacht and the Police for the “atrocities committed by fascist invaders on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR”. The Military Tribunal convicted fifteen war criminals, including Paul Sheer commander of the Police in Kyiv and Friedrich Jeckeln Higher SS and Police Commander in Ukraine. The charges against them both did specifically include the organisation of the murder of Jews in areas under their jurisdiction.

Witnesses gave harrowing testimony to the Tribunal of the massacre, prominent was Dina Pronicheva a Ukrainian Jewish theatrical actress who miraculously escaped Babyn Yar by pretending to be dead.

On 29 January 1946, thousands turned out to see the war criminals, including three Generals, hanged on what is now the Maidan Nezalezhnosti in the centre of Kyiv. But despite the public desire for justice still no monument was yet built for the victims at Babyn Yar.

The approach of the Stalinist bureaucracy to the memory of Babyn Yar was at first contradictory, combining honest recognition and obfuscation of the Holocaust, retrogression deepened as a state sponsored antisemitism was ratcheted up.

The Struggle for the Memory of Babyn Yar

Initially the central Soviet press reported the killing of Jews at Babyn Yar and did not hide the antisemitic nature of the massacre. On 19 November 1941 Izvestiia carried an article entitled ‘Atrocities of the Germans in Kyiv’, reporting that “the Germans killed 52,000 Jews in Kyiv – men, women, and children”, on 29 November Pravda described it as a ‘pogrom’ which killed 52,000 including Ukrainians and Russians.

An official report by Vyacheslav Molotov, Commissar for Foreign Affairs did detail the massacre and recognised the Jews were singled out for lethally special treatment in Kyiv. But when ‘Molotov’s Note’ was reported on 7 January 1942 in Izvestiia it downplayed the anti-Jewish nature of the massacre referring to the murder of ‘Ukrainians, Russians, and Jews who gave any sign of their loyalty to Soviet rule’. Following the liberation of Kyiv in 1943 new eyewitness accounts of Babyn Yar were published in Izvestiia and the Red Army paper Krasnaya Zvezda. Numerous articles appeared in Eynikayt the Yiddish language paper of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC), including by prominent writers such as Ilya Ehrenburg.

In November 1943 an official ‘Extraordinary State Commission for the Establishment and Investigation of Atrocities of the German Fascists Invaders’, (ChGK) began work in the Ukrainian SSR. The ChGK investigation did provide an accurate account of how the Nazi’s “herded the Jews who had assembled to Babyn Yar, confiscated all their valuables, and then shot them.” But once their daft report was sent to Moscow for approval by the Communist Party leadership, changes were imposed by senior figures. Georgy Aleksandrov head of the Propaganda and Agitation Department of the Central Committee removed all reference to Jews as victims; both Molotov and Nikita Krushchev had a hand in this editing. When the final report was published in 1944 the language was changed, from ‘Hitlers bandits’ having carried out a ‘mass brutal extermination of the Jewish population’, to them having ‘drove thousands of peaceful Soviet citizens’ to Babyn Yar.

This was the shape of things to come in terms of such concealment of the antisemitic nature of the largest element of the Babyn Yar massacre.

Despite this there were courageous attempts by Jewish, Ukrainian and Russian writers to accurately respect the memory of the massacre. Particularly active were the members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC) and Writers Union of Ukraine. A number of articles appeared in the JAC journal Eynikayt on Babyn Yar, on the anniversary in 1944 a notable piece by Itzik Kipnis ‘Babyn Yar, To the Third Anniversary’, appeared in Yiddish and Russian. He wrote of the anguish felt by the Jews exacerbated by what was viewed as the indifference of Ukrainians.

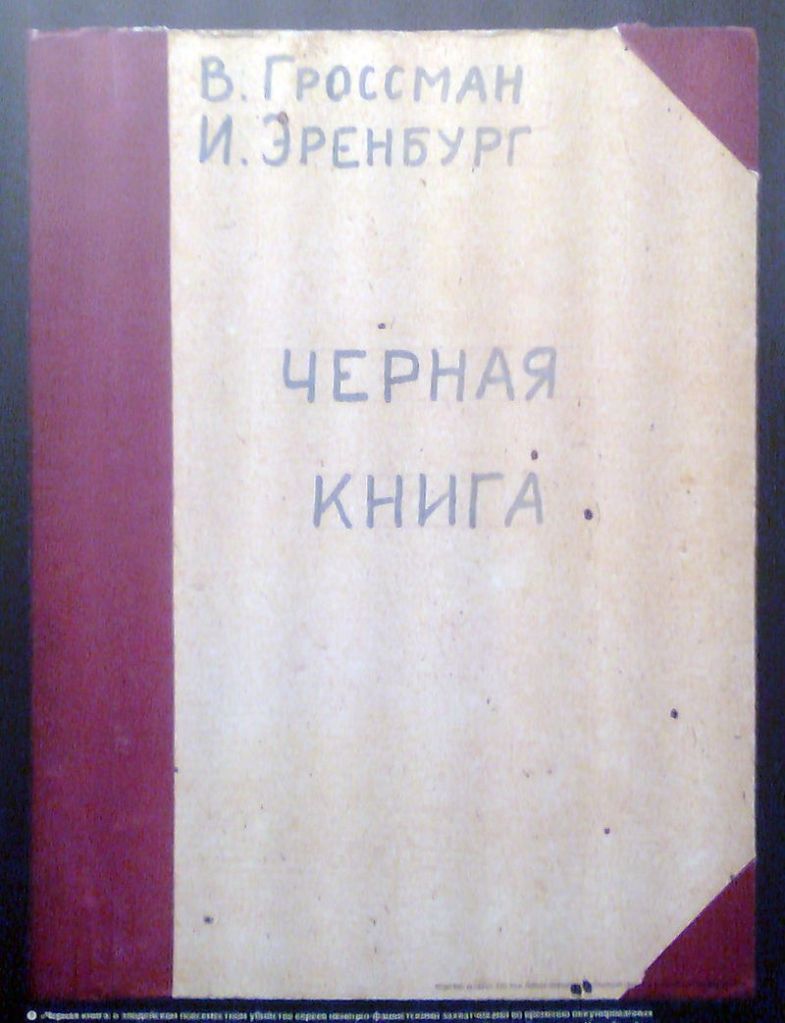

In August 1944 the JAC had sought to publish The Black Book as an account of Nazi atrocities in the USSR and camps in Poland, compiled by Ukrainian Jews, Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman with a foreword by Albert Einstein. Deeply moved by Babyn Yar, Ehrenburg had been with the Red Army when the city was liberated and saw the burial pits for himself. Whilst published internationally it met obstacles in the Soviet Union, at first sections were published in Yiddish, then it was censored to conceal the place of Jews in the massacre, then in 1948 it was cancelled completely. It was not published in Ukraine until 1991.

In September 1944 another JAC member, the poet David Hofstein returned to Kyiv and tried to organise a demonstration of the Jewish population to mark the third anniversary of the Babyn Yar massacre. Hofstein was refused, the authorities considered it would be ‘harmful’ and provoke antisemitism. This perverse reasoning, which saw the Stalinist authorities resort to antisemitism under the guise of opposing it was common to sections of the bureaucracy reluctant to recognise Jews had suffered any more than others. Khrushchev, the Kremlin appointed, First Secretary of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine (KP(b)U), was known to argue Jews should not be appointed to leadership positions as it would attract hostility that could turn into antisemitism.

Nevertheless, without official sanction a spontaneous commemoration of the massacre did take place in 1944, and ‘from early morning till late evening, masses of people… military men, workers, public servants, women with children, young and elderly’ went to Babyn Yar. Many workplaces decided to allow Jewish workers to take time off to visit the site, a survivor Nesia Elgort recalled being permitted to take a day off ‘in order to visit the “vale of tears” and give vent to her grief….’.

After this prominent voices continued to be heard for recognition of the Babyn Yar massacre. On 9 January 1945, Radyansʹka Ukrayina the central newspaper of the Ukrainian SSR published an essay by the author Rafail Skomorovsky entitled ‘We Shall Not Forget, We Shall Not Forgive! The Blood Soaked Ravine’. The article cited the eyewitness testimony of a Ukrainian Tamara Mikhaseva who had a Jewish husband, in which she highlighted the special attitude of the Nazis towards Jews as seen at Babyn Yar.

Even before the final German defeat there were calls for a memorial monument to be constructed at Babyn Yar. On 13 March 1945, the Government of the Ukrainian SSR and Central Committee of the (KP(b)U) agreed to construct a monument. In July 1945 the JAC paper Eynikayt carried a report on the monument and allocation of state funds. During 1945 – 1947 planning for the monument was underway, half of the three million rubles needed was allocated by 1946, the City Council ordered chief architect Alexander Vlasov to plan the new territory of Babyn Yar. The artists and architects were all appointed to work on the designs.

The planned monument was a black granite pyramid, with two sculptures at the entrance, surrounded by tree lines paths and gardens. It was to have been built during 1945-1947 but construction was delayed with only half the budget allocated by 1946. The Ministry of Culture criticised the design for its ‘pitiful appearance’, but it was not the design that was the problem, the project was permanently deferred due to the realignment of the Stalinist policy. The post-war years in the USSR became characterised by a state campaign of antisemitism, there was widespread displacement of Jews from the Soviet state apparatus such as the diplomatic service, Communist Party, military HQ and security structures.

Babyn Yar was not alone; in 1947 in Poltava, Chernihiv and other regions of the Ukrainian SSR permission was refused for monuments to Jewish victims of the Nazis. In Kamianets-Podilskyi a memorial event to mark the murder of the Jewish community was refused by city authorities, there was similar obstruction to a campaign to dismantle pavements made of Jewish gravestones.

Why did a state that had just liberated Auschwitz and defeated Hitler engage in such discrimination and de-recognition of the Holocaust? The explanation can be found not in the start of the Cold War or the Kremlin abandoning support for Israel, but as a response to internal opposition and a potential challenge to Stalinist rulers.

Stalinist retrogression, Ukrainophobia and antisemitism

The war had radically changed the political situation in the Ukrainian SSR, when the invasion began the official ideology was bankrupt, the peasantry and workers did not believe in Stalinist state socialism, there was significant defeatism. In Western Ukraine which was incorporated into the USSR in 1939, Leon Trotsky observed a ‘state of confusion’ resulting in illusions in the Germans. But the scale of this across Ukraine is grossly exaggerated. Of the citizens of the USSR who fought with the Germans a mere 16 per-cent came from Ukraine. Nazi efforts to exploit experiences of Stalinism in pre-1939 Soviet Ukraine ended in failure, within a year Reichskommissar Koch bemoaned: ‘The population’s passive resistance has escalated significantly’.

During the war there was a surge in national self-consciousness, a form of Soviet Ukrainian patriotism was expressed in the ‘people’s war’ with the populace called upon to defend ‘our Ukrainian statehood’, language and culture. The Stalinist regime had to make concessions to this Ukrainian national consciousness in order to harness it for the war. On the ground Ukrainian intellectuals and communists grasped the opportunity with a mass campaign invoking the traditions of Ukraine’s liberation struggles in the fight against Hitler.

An estimated 357,000 joined red partisans in Ukraine, some tried to be independent of the Russian command. Up to seven million from Ukraine fought in the ranks of the Red Army and Red Fleet. This movement is the true story of Ukraine in World War Two be celebrated. Buoyed by victory they looked to a different post-war life, the Ukrainian communists and intelligentsia with their relative autonomy, attempted to continue the momentum of the wartime struggle.

To the bureaucratic elite seeking to restore its authority this was a potential opposition to be stifled and concessions ended. A hard-line ideological policy was introduced in August 1946, outlined by Stalin’s henchman Andrey Zhdanov, justified by the possible risk posed by inhabitants of territories ‘occupied by the enemy’, those ‘deported to Germany’, prisoners of war and troops who had advanced into the ‘territory of capitalist states’. As Ukraine had been fully occupied the crackdown was widespread, many intellectuals were persecuted for ‘national deviations’, large numbers removed from Party posts and membership.

The Zhdanovshchina continued up to Stalin’s death in March 1953, and it was accompanied by a wave of Russian Chauvinism which had begun with Stalin’s historic toast at the Kremlin banquet in May 1945 honouring Russia as the ‘outstanding nation in the USSR’. Previously Russian Tsarism had fostered antisemitism as a means of combatting the revolutionary movement and diverting grievances. With Stalinism glorifying the era of the Tsarist Empire, such antisemitism logically followed from this Russian chauvinism. In this the Soviet authorities saw a direct link between the memory of the holocaust and potential opposition.

From 1946 onwards a powerful state campaign was ratcheted up with exhortations against ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism and rootless cosmopolitans’ clearly aimed at Jews. There was widespread attacks on ‘Jewish bourgeois nationalists and Zionists’, with purges of alleged ‘Zionists’ and the scapegoating of Ukrainian Jews.

The Jewish section of the Writers Union of Ukraine was dissolved in January 1949., and the Office for the Study of Jewish Literature at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, which had collected Holocaust testimonies, was closed in 1950.

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee which had been at the forefront of seeking recognition of Babyn Yar was closed down in October 1948. Accused by the Politburo as a ‘centre of anti-Soviet propaganda’ 110 people linked to the JAC were arrested, following forced confessions thirteen prominent Jewish literary figures faced a show trial in 1952, five of them from Ukraine including Hofstein and Fefer. They were all executed in Moscow on 12 August 1952.

This antisemitism did not push up from below, with the bureaucratic elite accommodating to existing prejudices to assist them in restoring their authority. It was a deliberate choice and orchestrated from above.

In Kyiv by 1947 the population was 700,000, being 60% Ukrainian and again 20% Jewish. But there was not an inherent hostility that had become predominant; it was the City authorities who caused difficulties such as in housing. There was sufficient housing stock, but the city authorities disregarded laws which assured homes such as for Nazi victims, soldiers and their families. Instead they adopted a first come first served policy which benefited the larger Ukrainian populace. (40,000 complaints by Kyivans were not addressed). Some returning Jews found their apartments occupied, with bureaucratic obstacles in their way. The city authorities sought to defuse grievances by stressing the Nazi’s crimes against Ukrainians and their culture, but ignoring the anti-Jewish element of the crimes.

In September 1945 there had been anti-Jewish violence in Kyiv linked to the housing problem. A Lieutenant Rosenstein was subject to antisemitic abuse and attacked by two soldiers aggrieved by a housing dispute – local residents assisted Rosenstein, who then found and shot his attackers. On the day of their funeral 300 attended and mourners attacked several Jews in site of the procession. The authorities intervened to prevent any further attacks.

Rumours spread widely that a pogrom had occurred, a letter about the violence was sent to Stalin and other leaders by former Jewish soldiers ‘, they wrote that: “The word “Jew” or “beat the Jews” – a favourite slogan of German fascists, Ukrainian nationalists and tsarist Black Hundreds – is heard on the streets of the capital of Ukraine, in trams and trolleybuses, in shops, in bazaars and even in some Soviet institutions”. All the Communists who signed the letter were arrested.

With the defeat of Nazi Germany there was an historic opportunity to address residual antisemitism in Ukraine, which would have included honest recognition of Babyn Yar and the Holocaust. An example of what was possible is the experience of the red partisans; Jews had different experiences of Soviet partisans, ranging from solidarity to callous indifference and violence. Crucially, particularly from 1942, there were efforts to combat antisemitism, disciplining offenders and arming survivors. Partisans aided Jews, for example a Chernihiv-Volyn unit in August 1942 stopped an attack on Jews hiding in woods, killing seven and wounding five Germans.

If this could be done by partisans we may ask what could have been done by the Soviet state with all the resources at its disposal. Instead Stalin chose the opposite.

The Desecration of Babyn Yar

With the death of Stalin in March 1953 an even larger purge and deportation of Jews was averted, but whilst the period of the ‘thaw’ saw aggressive antisemitism recede it remained present under the campaign against ‘international Zionism’. In the following years many monuments were being erected at sites of Nazi atrocities across the USSR, Babyn Yar however became a scene of desecration.

In March 1950, the authorities of Kyiv and the Ukrainian SSR, with a focus on their post-war construction plans decided on a new use for Babyn Yar. With the need to significantly increase brick production they decided to use the ravine for waste produced by the nearby Petrovsky brick factories. Under Krushchev rapid housing construction plans saw the factories working continuously with the waste mounting on the mass graves behind a poorly constructed dam.

In 1957 the Central Committee of the KPU discussed Babyn Yar again and decided not to erect a monument. Instead, plans were considered to erect a sports stadium and further housing developments. When the plans became known they provoked outrage, the prominent Kyiv born writer Viktor Nekrasov wrote in Literaturnaya Gazeta in October 1959 that hardly a family in Kyiv was untouched by the massacre at Babyn Yar, he questioned what has happened to the previous plans for a monument, as to the latest plans he asked could this really be possible?

No, that cannot be allowed! When a human being dies, he is buried and the grave is marked. Can anyone possibly believe that this tribute of respect was not deserved by the 195,000 people viciously shot at Babyn Yar, at Syretsky, at Darnita, at the Kirillov Hospital, at the monastery at the Lukianovksii Cemetery?

Viktor Nekrasov

In December a further letter appeared in Literaturnaya Gazeta by a number of residents of Kyiv supporting Nekrasov. In March 1960 there was an official response from the Executive Committee of Kyiv City Council, with the excuse no monument had been built at Babyn Yar due to the condition of the ravine, but the Soviet Ukrainian government had decided to construct a park with an obelisk in the centre to the memory of the murdered Soviet citizens.

The decision, if true was again not implemented. But Babyn Yar now became the scene of further tragedy – what became known was the Kurenivka tragedy. Warnings by local residents of water leaking through the dam were ignored, then following heavy rain the ten years of waste broke through the dam on 13 March 1961. A torrent of mud and human remains flooding into the nearby Kurenivka district of Kyiv. Officially 145 people died, recent studies estimate 1,500 died. People called it the ‘revenge of Babyn Yar.

Hearing of the disaster the Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko travelled to Kyiv accompanied with Anatoly Kuznetsov, who was working on a novel about Babyn Yar. Yevtushenko recalled: “I knew that there was no monument there, but I expected to see some memorial sign or some well-groomed place, “Before our eyes, trucks drove up and dumped more and more piles of garbage on the place where these victims lay”. In his view the main reason for there being no monument was the fact that mostly Jews were murdered at Babyn Yar.

Soon his visit after Yevtushenko read his poem ‘Babyn Yar’ in public at the October Palace in Kyiv, then published it in Literaturnaya Gazeta, on 19 September 1961 to commemorate the 20th Anniversary of the massacre. The opening line declared: ‘No monument stands over Babi Yar’, it received many positive responses from readers. But within days Yevtushenko was subject to a series of attacks in the journal Literature and Life, the Russian poet Aleksei Markov accusing Yevtushenko of defiling the memory of Russian soldiers using standard antisemitic code he wrote: “As long as graveyards are trampled by even a single cosmopolite, I say : People, I am a Russian!”. A further article by D Starikov denounced him for a ‘retreat from communist ideology to a bourgeois ideology’, finding only antisemitism in the massacres and claimed Ehrenburg did not classify the dead by nationality. Ehrenburg himself wrote to Literaturnaya Gazeta in October 1961 disassociating himself from Starikov.

The controversy continued when the composer Shostakovich put Yevtushenko’s poem Babyn Yar to music in his Thirteenth Symphony. On 17 December 1962, the day before it’s premier, the Soviet leader Khrushchev convened a meeting of 400 members of the intelligentsia. At the meeting Ilya Ehrenburg was accused of having betrayed his former comrades in the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Yevtushenko ended his own speech by quoting his poem Babyn Yar. He was in turn attacked by Khrushchev who claimed antisemitism was not a problem in the USSR, he repeated his opinion Jew’s should not hold senior posts as it provoked resentment, claiming this was the cause of the 1956 revolution in Hungary. Courageously Yevtushenko countered and said it was a serious problem demanding measures to address it.

Pressure was then exerted on Shostakovich to cancel the premiere of his Thirteenth Symphony, he and Yevtuschenko refused. It proceeded but on the third day it was cancelled after they were warned it would be banned completely. Changes were then imposed on the text such as ‘I think of Russia’s exploit’, Then ‘it barred the way to Fascism with its own body..’ There was no special recognition of Jews alongside the Ukrainian and Russian victims.

On 8 March 1963, at a meeting of 600 Soviet writers Khrushchev again attacked Yevtushenko over Babyn Yar. It was a lie he said, to claim there was discrimination against Jews in the USSR. The poem ‘Babyn Yar’, ‘represents things as if only Jews were the victims of the fascist atrocities, whereas, of course, the Hitlerite butchers murdered many Russians, Ukrainians and Soviet people of other nationalities.’

Whilst the Soviet leadership was attacking Yevtushenko on the ground at Babyn Yar the desecration continued. The area was being levelled for new building works; the Jewish cemetery flattened for construction.

In October 1964 Khruschev was removed and replaced by Kosygin as Premiere, and Brezhnev became First Secretary of the CPSU. The post-war thaw did not end immediately, however. Perhaps to differentiate from their predecessor Kosygin made several speeches attacking antisemitism and Shostakovich’s symphony was allowed to be play again. Then on November 30, 1965, Literaturnaya Gazeta announced that the government of the Ukrainian SSR had decided, again, to build monuments at Babyn Yar. One to commemorate the victims of the massacre and another, the inmates of the concentration camp. Architects were invited to submit proposed plans for consideration, regardless the bulldozers continued to work on Babyn Yar.

On this occasion sixty models of proposed monuments were displayed in an exhibition at the House of Architeture in 1965. The selection panel rejected all the proposals, describing that of Josif Karakis and Aba Meletsky for a memorial park as Zionist. A second competition was announced, this time with more conformist proposals – they too were rejected by the First Secretary of the KPU Petro Shelest.

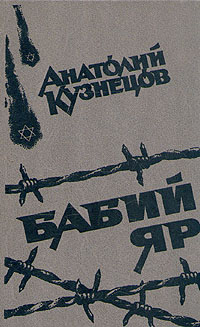

In 1966 another work appeared which sought to challenge the situation, this time by the Alexander Kuznetsov who like his friend Yevtushenko he was not himself Jewish. He had grown up near Babyn Yar and from his childhood years he kept a notebook of what he witnessed under the occupation. His work Babyn Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel was published in the journal Yunost in autumn 1966.Though censored it was widely acclaimed, it also put in the public domain what everyone knew to be the case – that the victims were in the majority Jewish. The novel was published in time for the 25th anniversary of the massacre and set the scene for people to take matters into their own hands in defiance of official neglect.

Twenty Five Years – Turning Point

Not long before the anniversary in 1966 the Jewish engineer and activist Emmanuel (Amik) Diamant visited the site with Anatoly Kuznetsov. He was shocked and took photographs for historical record of the lack of respect and dignity for the victims buried there – a scene of waste, construction works and human remains still visible after a quarter century.

On 24 September some young Jewish activists led by Diamant went to the old Jewish cemetery and raised a banner with inscriptions in Russian and Hebrew “Babyn Yar. ‘1941 September 1966, ‘Remember the 6 million’. A few days later to mark 25th anniversary of the start of the massacre at Babyn Yar, the writer Viktor Nekrasov had taken the lead to organise a public demonstration at the site in defiance of the official silence – it would prove a turning point.

The 25th anniversary of Babyn Yar was at a time of significant ferment in Ukraine. A broad current of radical youth known as the shestydesiatnyky – ‘generation of the sixties’ was actively seeking cultural and political reform. In the 1965 the authorities responded with house searches and arrest of one hundred people, between January-April 1966 twenty of them were put on trial and sixteen imprisoned. There were numerous public protests, at the forefront was the Marxist dissident Ivan Dzyuba, a leading Ukrainian literary figure. In protest Dzyuba submitted to leaders of the Communist Party and Government of the Ukrainian SSR a lengthy petition – the book Internationalism or Russification. It was widely circulated, inside the Party, underground and published abroad by the western socialist movement.

In Internationalism or Russification Dzyuba called for a ‘resolute struggle against Russian Great-Power chauvinism as the main threat to communism and internationalism’ and a ‘restoration of the Leninist nationalities policy’ which had saw the Ukrainian cultural renaissance of the 1920s. Dzyuba also challenged antisemitism, noting that just like Russian Chauvinism:

Until recently the existence of anti-Semitism in the USSR has been denied in the same way. Heavens, what а mortal sin and tactlessness, what political illiteracy it was to mention anti-Semitism! Khrushchev was foaming at the mouth trying to prove that such questions were paid for in American dollars. …… And now, after so many Ciceroniads, Jeremiads, Lazariads and Nikitiads, it has seemingly been decided to return to Lenin: Pravda in its leading article of 5 September 1965 calls, in Lenin’s words, for а ‘tireless “struggle against anti-Semitism” ‘. Well, it is good that this has been said at least belatedly, though it could have been said much earlier! They said it and … filed the newspaper. But when and how will this ‘tireless struggle’ begin?

Ivan Dzyuba Internationalism or Russification

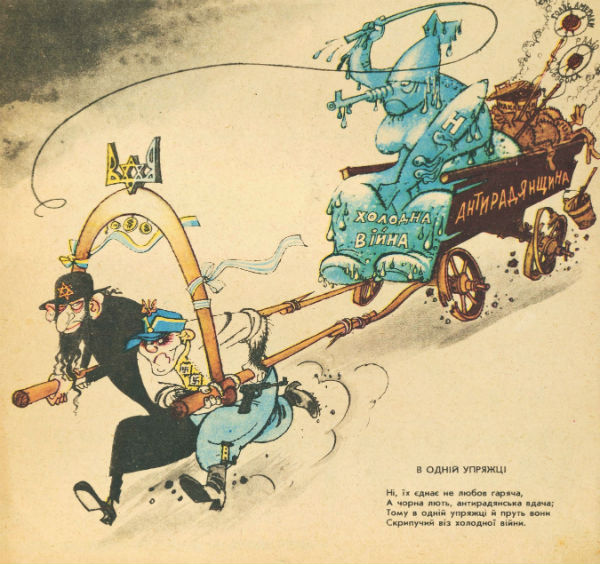

At first there was no official response to Dzyuba, then in June 1966 in the paper Komunist Ukrainy the Secretary of the Kyiv KPU attacked his ‘ideologically harmful statements’, to be followed in September by an attack in the satirical magazine Perets .

This was the situation when in Diamant’s words 1966 became ‘in peoples memory the year of the first mass uprising against the violence committed at Babyn Yar’. It was normal for individuals to go to Babyn Yar and place flowers, after a quarter century in became an unofficial rally of over a thousand people.

Jewish activists and survivors were joined in solidarity by Russians and Ukrainians. Viktor Nekrasov and the old Ukrainian Communist from the revolution Borys Antonenko-Davydovych spoke, most prominent of the speakers was Dzyuba. He recalled how people were silent, the crowd surrounded them and ‘demanded “Say something, at least something!” One had to improvise, though we spoke about what we well knew and was hurting inside.’

In a powerful speech to the rally Dzyuba said: “Babyn Yar is a tragedy of all mankind, but it happened on Ukrainian soil. And therefore, a Ukrainian has no right to forget it anymore than a Jew. Babyn Yar is our common tragedy, a tragedy for both the Jewish and Ukrainian nations.” It had been brought to them by fascism, and they were gathered to ‘commemorate the sacrifices and efforts of millions of Soviet citizens of all nationalities who unselfishly contributed to the victory over fascism. We should remember this so that we may be worthy of their memory, and of the duty which has been imposed upon us by the countless human sacrifices, hopes, and aspirations that were made.’

Dzyuba sharply condemned antisemitism and the failures of the Soviet government: ‘But what is strange is the fact that no struggle has been waged here against it during the post war decades; what is more, it has often been artificially nourished. It seems that Lenin’s instructions concerning the “struggle against antisemitism are forgotten in the same way as his precepts regarding national development of the Ukraine.’

Dzyuba recalled how Stalin had sought ‘to use prejudices as a means of playing off Ukrainians and Jews against each other—to limit the Jewish national culture on the pretext of Jewish bourgeois nationalism, Zionism, and so on, and to suppress the Ukrainian national culture on the pretext of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism.’ Declaring that: ‘As a Ukrainian, I am ashamed that, as in other nations, there is antisemitism here; that those shameful phenomena which we call antisemitism— [and which are] unworthy of mankind—exist here.’ He called on Ukrainians to fight against all manifestations of such hatred: ‘There is nothing more important for us at the present time, because without such opposition all our social ideals will lose their meaning.’

Dzyuba appealed for Jews and Ukrainians to recognise that their common past consisted ‘not only of blind enmity and bitter misunderstanding’ but that it ‘also shows examples of courageous solidarity and cooperation in the fight for our common ideals of freedom and justice, for the well-being of our nations.’

The speeches were circulated unofficially in Samizdat, the KGB confiscated the film of the rally, the speech of Dzyuba’s would later be cited in evidence against him – he was imprisoned in 1973.

Despite the repression the rally was a turning point for the memory of Babyn Yar. In October 1966 the Party and Kyiv authorities decided to install a memorial stone with the inscription “A monument to the Soviet people – victims of fascist atrocities during the temporary occupation of Kyiv in 1941-1943” will be erected here.

Every year the Soviet Authorities now held an official commemoration on the anniversary of the Babyn Yar massacre. These bureaucratic rallies of ‘workers dedicated to the victims of fascism’, though were without specific reference to the Jewish victims. Alongside the official commemorations unofficial memorial events took place. In 1971 several hundred Jews gathered at Babyn Yar, it became a site of commemoration of the massacre and a protest at state antisemitism.

A monument was finally constructed by the Soviet Ukrainian government on 2 July 1976, it declared: “Here in 1941-1943, more than a hundred thousand citizens of the city of Kyiv and prisoners of war were shot by German-Fascist invaders.” It was final recognition of the dead but not of the antisemitic nature of the mass murder. Furthermore, the decades of struggle had prevented the complete desecration of the site – such as it being turned into a sport complex.

A Public Historical Education Centre was not opened at Babyn Yar until 1980, even then, until the USSR collapsed there was recognition of the massacre but not it’s full nature. Not until 19 September 1991, fifty years after the massacre did Leonid Kravchuk the head of the Parliament of newly independent Ukraine, acknowledge the majority killed were Jews, murdered only because they were Jews and he issued an apology to the Jewish community for the years of supressing the truth about Babyn Yar.

In reviewing the eighty years since the massacre it can be concluded that there is now the greater recognition not only of the diversity of victims at Babyn Yar, but of the specific antisemitic nature of the largest massacres. Indeed over thirty monuments and plaques are now erected. There is greater official recognition, commemoration and education in Ukraine today of the Babyn Yar and the Holocaust in general. The work of such civil society bodies like ‘Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies’ is of significant value, as is the array of local grassroots initiatives to restore neglected sites of historical memory from this tragic period.

However, the progress achieved is coupled with deep retrogression in contemporary Ukraine, there is still a tendency as in the Soviet era, for a disproportionate shifting of emphasis that others also died at Babyn Yar.

There are two aspects of current retrogression which are of concern to the memory of Babyn Yar. One is linked to the ongoing aggression of Russian Imperialism towards Ukraine. This aggression has sought to camouflage itself in language of ‘anti-fascism’ and is accompanied by Putin’s supporters internationally who portray Ukraine as a ‘quasi-fascist’ or ‘semi-fascist’ state. This is a gross insult to the memory of the victims of the actual fascist period of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine of which contemporary Ukraine bears no resemblance.

The second area of retrogression arises from the nature of Ukraine. Since independence the big business power of the oligarchs has been the dominant influence on the politics and economy of Ukraine. As part of the effort of the ruler to legitimise this system they have constructed an official history which has sought to glorify the most conservative figures of Ukraine’s of struggle for greater freedom and independence. Whilst sanitising this history of it’s radical and socialist elements. In so doing they have also glorified wartime Nationalists, whilst presenting them as also opponents of Hitler they are also whitewashing their collaborationist role.

Symptomatic is that on 13 June 2021, the funeral of a member of the SS, Orest Vaskul took place in Kyiv, he was afforded military honours by the Presidential Regiment. Eighty years earlier the same SS was poised to begin their murderous journey to Kyiv which would result in the Babyn Yar massacre. There can be no reconciliation in honouring the memory of the victims and the perpetrators of the crime – in such circumstances it cannot be concluded the victims of Babyn Yar have yet secured historical justice.